Chasing after Philippine artifacts in Madrid

A recent trip abroad to spend time with family and friends was underscored by a personal search mission to uncover Philippine art and artifacts lying under the radar. I was inspired both by hearsay and urban legend as well as by an ongoing research project coordinated by the School of Oriental and Asian Studies (SOAS) in London, led by the tireless Philippine academic, Dr. Cristina Juan, and co-edited by the curator Marian Pastor Roces.

The project, “Mapping Philippine Material Culture,” simply put, is a massive digital effort to put together an open-access database of Philippine objects in collections outside the Philippines. It serves as a useful guide to digitally exploring Philippine objects in various locations all over the world, from Europe to Asia.

For obvious reasons, Spain has a myriad of Philippine objects to explore in many institutions and collections referred to in the aforementioned website. I made a plan to meet up with two intrepid Europe-based Filipina friends in Madrid who were game to explore along with me.

Our first stop was the Museo de America in the Moncloa district. The imposing building from 1940’s Franco-ruled Spain is home to ethnographic and archaeological collections amassed during the Spanish empire’s height from the 15th to 19th centuries from its territories in the Americas and beyond, including the Philippines. The famed five-year Malaspina Expedition of 1789-94 was one such scientific voyage that sought to confirm and sharpen details of navigational routes, as well as delve into the economic and anthropological state of Spanish territories.

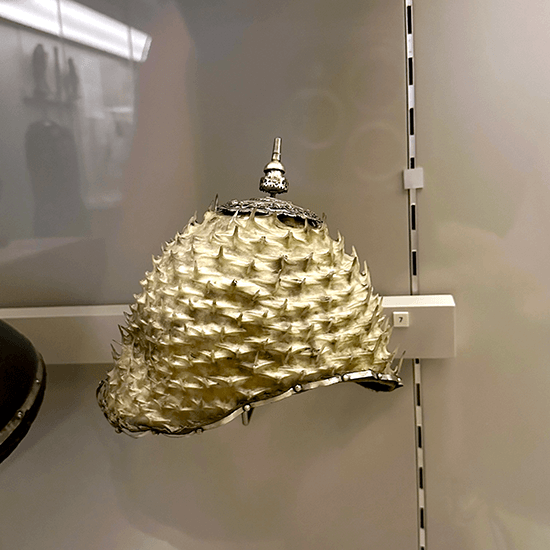

Most of the Philippine artifacts on display at the Museo de America were likely gathered during the Malaspina Expedition. Most were housed in large wooden and glass cabinets in a seemingly deliberate aesthetic reference to past centuries wherein scientific discoveries brought about the rise of cabinets of curiosities, or display rooms; which in turn eventually led to the development of the modern museum.

Philippine objects on display included shells, woven hats and baskets, and weaponry such as shields and knives. The atmosphere of a past era of exploration and discovery à la Indiana Jones was accentuated by the original faded paper tags attached to the displayed items, with accession numbers written in florid penmanship in now-faded ink, a fascinating detail. The only other significant Philippine object we spotted was an intimidating, infant-sized carved ivory of a rather fleshy Santo Niño figure from the 17th century.

On a whim, after a brief break for lunch, we decided to try and view the fabled Juan Luna masterpiece, The Battle of Lepanto of 1571, which is installed in the Palacio de Senado. This famous work is not readily available to view publicly, as we learned to our chagrin, upon arriving there. We were waved away by a rather stern receptionist who told us that a visit was not possible without permission requested in writing or a call in advance. Our pleadings about wanting to see the work of a fellow Filipino as well as our short stay in Madrid fell on deaf ears, and we left, quite dejected at the rejection. To our surprise, we were soon followed outside by a pair of guards, who offered to accompany us to an alternative entrance, away from the gaze of the unbending receptionist. They said they wanted us to leave Madrid with a “good impression of España.”

One could easily gain a capsule history of Philippine cultural artifacts, albeit from a 19th-century point of view.

After a circuitous walk, we entered through another guarded entrance, and soon came across Luna’s masterpiece. Despite the cramped viewing space, being situated in a narrow corridor, the painting was truly a sight to behold. Its huge dimensions—11.5 x 18 feet—as well as the complex composition of the battle scene brought home to the viewer that the work was truly a bold and daring enterprise on Luna’s part. A commission from the Spanish Senate, Luna finished the work in 1887, and won a gold medal for it the following year, in Barcelona.

The Battle of Lepanto was a famous Christian victory over Muslims of the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century. A tough sea battle involving hundreds of ships and thousands of men, Luna chose to depict the Spanish naval hero Don Juan de Austria commanding one of the Spanish ships. The bloodied soldiers, the dead and the half-drowned souls struggling to survive by clinging to wooden ship remnants are masterfully depicted by Luna with swift, expressive brushstrokes. According to our kind and well-informed police escort, the famed Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes lost one of his hands as a young soldier in this battle. We eventually left the Palacio de Senado, overjoyed with our unexpected good fortune and the thrill of seeing Luna’s work; and definitely with a good impression of España.

The next day’s visit to the Museo Nacional de Antropologia situated near the Atocha train station yielded a surprisingly large trove of Philippine objects. Most of the ground floor was devoted to displaying items that were exhibited in the 1887 “Exposicion General de Filipinas,” an exhibition intended to further Spain’s Philippine colonial project by showcasing its arts, culture and economy. Expositions and world’s fairs were then a popular global activity. (1887 happens to be the same year Luna finished the Lepanto painting.) Held in the El Retiro park of Madrid, the exhibition was controversial among the Filipino ilustrados in Madrid, including Jose Rizal, who felt that the exhibition of members of Philippine ethnic groups was oppressive and inhuman.

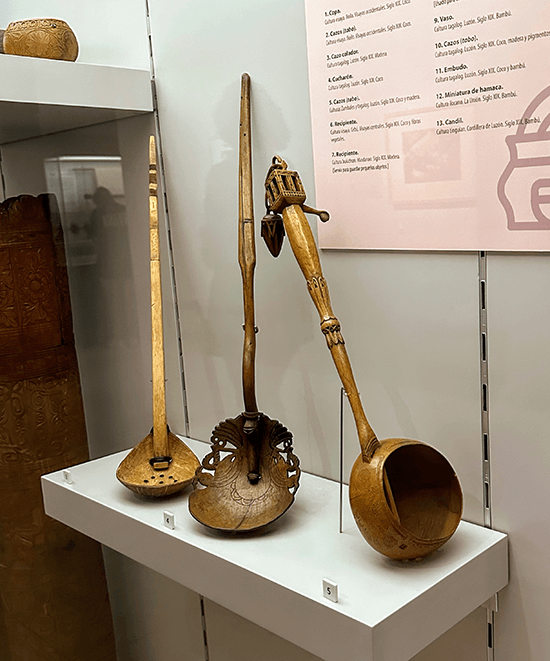

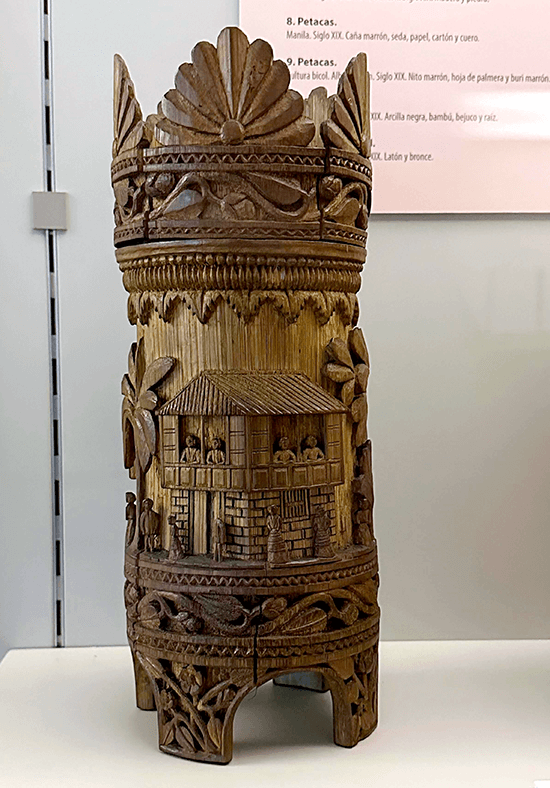

Notwithstanding this culturally sensitive historical issue, the variety and scope of objects on display was impressive—musical instruments, traditional toys, tobacco containers, baskets, agricultural implements, weaponry, hats, jewelry, textile and embroidery, models of Philippine dwellings and more. A central double-height room displayed two huge Philippine wooden longboats hanging from the ceiling, allowing a view of their hulls from beneath. Several contemporary photographs showed the interiors of the exhibition pavilions within the Retiro park.

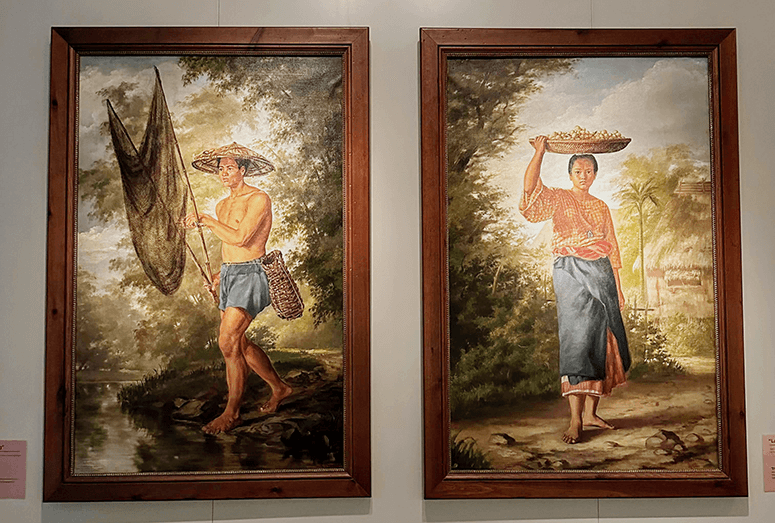

It was gratifying to see the 1887 exhibition items thoughtfully and carefully displayed, accompanied by well-researched text and descriptive labels. One could easily gain a capsule history of Philippine cultural artifacts, albeit from a 19th-century point of view. Towards the end of the exhibit, hanging innocuously on a wall was a beautifully executed pair of Philippine “types” rendered by the painter Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo —the male figure, a fisherman casting his bamboo trap in a river; and the female figure, a vendor of lanzones piled up in a bilao delicately balanced on her head. Both paintings were on loan from the Prado Museum.

Madrid was a treasure trove for this newly begun undertaking of mine to search of Philippine material culture abroad. The effort of seeking out these artifacts turned out to be an unexpectedly fulfilling cultural tourism activity, as I strayed away from the usual tourist pathways. I felt that I had only scratched the surface of a tantalizing cache of objects, as many other items mentioned in the Philippine studies database were in less accessible collections, and often, not publicly displayed.

With more advance preparation, and perhaps with written requests as advised by the Palacio del Senado’s unyielding receptionist, I hope to explore further and continue this personal mission of Philippine-focused cultural tourism in future visits to Spain and other countries.

* * *

“Mapping Philippine Material Culture” can be accessed through the website philippinestudies.uk.