Windows on the Filipino soul

Soon turning 80, the veteran journalist and fictionist Amadis Ma. Guerrero has added another feather to his cap as one of this country’s foremost chroniclers of culture, particularly the visual arts.

Less than two years ago, he gave us the splendid book Philippine Social Realists (Quezon City: Erehwon Artworld Corp.), where he reviewed 10 of the country’s most accomplished advocates of social realism, prompting The Philippine Star's Juaniyo Arcellana to call him “a master of reportage, which he puts to good use in this series of portraits of the artist as Philippine social realist.”

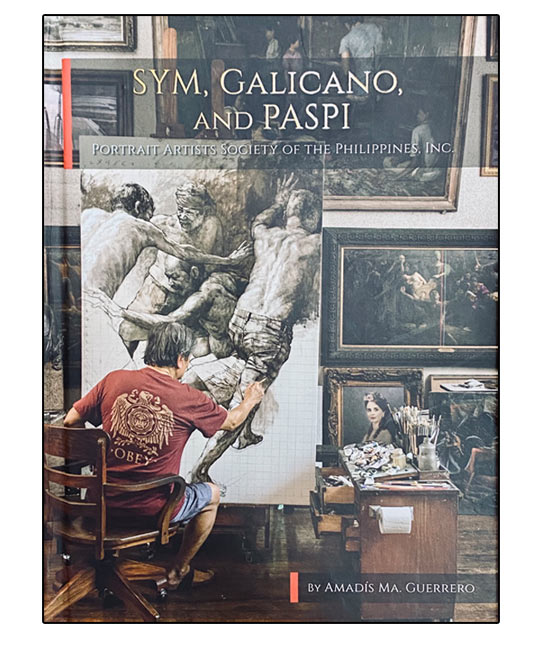

This time, with the launch last week of SYM, Galicano, and PASPI, also published by Erehwon, Guerrero takes on the art of portraiture itself, and the Filipino artists who have devoted themselves to — and distinguished themselves in — this most difficult of artistic challenges.

Say the word “portrait” and what will likely spring to mind for most Filipinos —excluding the “Mona Lisa” — is Jose Rizal looking pensive and noble, as he should, frozen in a print that has become almost obligatory in most government offices (at least until certain presidents and lesser politicians deemed themselves worthier of that spot on the wall).

The older and well-heeled crowd will default to Fernando Amorsolo, who seems to have painted everyone’s rich and famous grandfather or grandmother.

The more art-savvy might bring up John Singer Sargent, Lucien Freud, Andy Warhol and Frida Kahlo.

Indeed, portraits have served throughout history to glorify the sitters and their families, made to order by the most talented painters of their time, and paid for by the most powerful patrons of that same era.

They were, and still are, quite frankly made for money, which usually meant a softer line here and a scatter of stardust there to idealize the hopefully happy subject.

Occasionally and perhaps increasingly, they have also been made for love — if not love of art itself, then (to venture sideways into more theatrical territory) of the subjects who became their artists’ muses if not their lovers, such as Andrew Wyeth’s Helga Testorf or Gustav Klimt’s Adele Bloch-Bauer.

In his overview of contemporary Philippine portraiture, Guerrero provides us not only with a visual feast of styles and talents but also with — in his own way — verbal portraits of the artists themselves: their back stories, their struggles, and how they came to see and use portraiture as their window on the Filipino soul.

The title of the book may be cryptic to many, so let’s explain that “SYM” is Sofronio Y. Mendoza, the brother-in-law of fellow portraitist Romulo “Mulong” Galicano, and that “PASPI” is the Portrait Artists Society of the Philippines, Inc., whose members the two masters have mentored.

In his typically well-wrought foreword, Dr. Patrick Flores notes how important it is that “the story of art that this publication tells does not begin in Manila, perceived to be the center of the solar system of the Philippine art world.

It rather unfolds in Carcar in Cebu. This in itself contributes to the body of literature on a species of Philippine art that takes root in and flourishes beyond the metropolitan privileges of Manila.”

Carcar was where both Mendoza and Galicano studied at the foot of Cebu’s pre-eminent postwar painter, Martino Abellana, the so-called “Amorsolo of the South.”

Both men have since overtaken their teacher to become mentors to a new generation of gifted portraitists in PASPI, and the book offers glimpses into the life and works of many of its members — Wilfredo Baldemor, Romeo Ballada, Publio Briones, Jr., Carlos Cadid, Wilfredo Cañete, Jr., Ariel Caratao, Ramon de Dios, Efren Enolva, Carlos Florido, Alvin Montano, Maridi Nivera, Joemarie Sanclaria, Dante Silverio (yes, the Dante Silverio), and Lita Wells.

Amadis Guerrero tells well-framed stories of the artists and their passions with great empathy and efficiency,

With the exception of the former Toyota coach and long-time art enthusiast, few of these names will be familiar to most Filipinos, although many have attained some degree of professional accomplishment.

Some, like Romy Ballada and Boboy Cañete, never went to art school (born poor, Cañete didn’t even get to high school), but their work is suffused with what matters most in portraiture: character — which, as a fictionist, I take to be the promise of a deeper story beyond the picture.

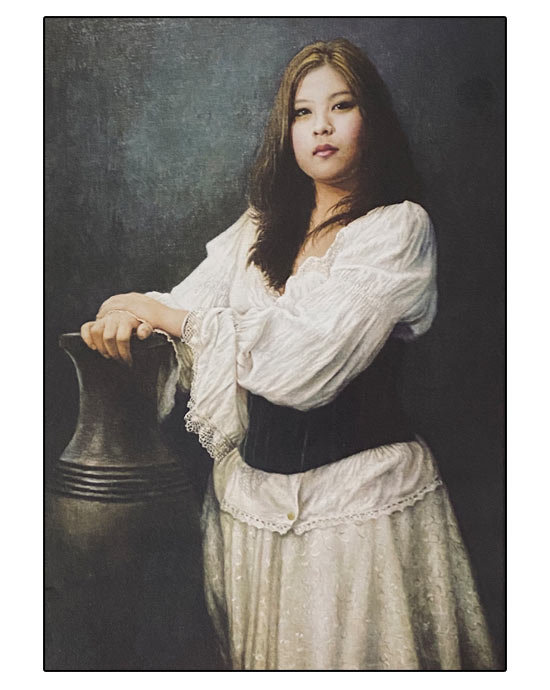

The stylistic range presented runs from the classically posed to the problematic postmodern, but I enjoy it best when the painter takes a break from his or her usual material, such as Galicano’s decidedly anti-romantic “The Sleeping Model.” (The book also explains why Galicano adopted his trademark stripe in his paintings.)

Amadis Guerrero tells well-framed stories of the artists and their passions with great empathy and efficiency, and I hope that he will be commissioned (as this is the only way this will happen here) to do full-length biographies of our National Artists such as Botong Francisco and Mang Enteng Manansala.

Also praiseworthy is Erehwon’s continuing commitment to art publishing, and to producing such handsome volumes (this one was designed and photographed by Willie de Vera). A recent winner of Quezon City’s Gawad Parangal for its leadership in the arts, Erehwon and its visionary founder, Raffy Benitez — who has sunk millions into his baby knowing he’ll never get it all back — deserve our gratitude and admiration.

Banner and thumbnail caption: Romulo Galicano’s “The Sleeping Model” (2020)