400 years of unfiltered history in 80 treasures

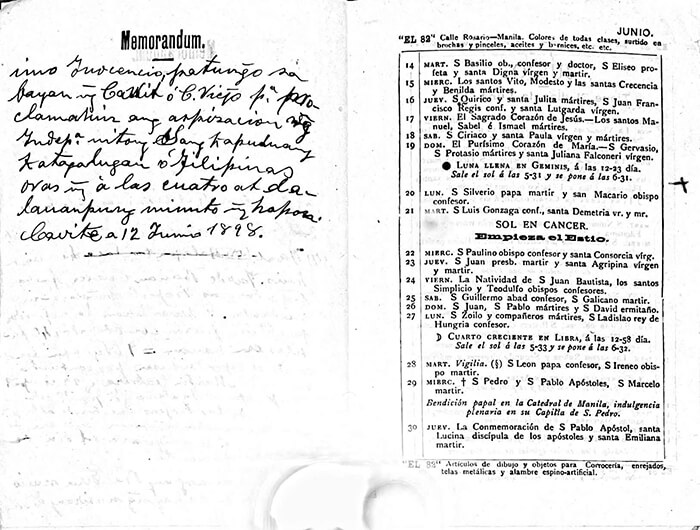

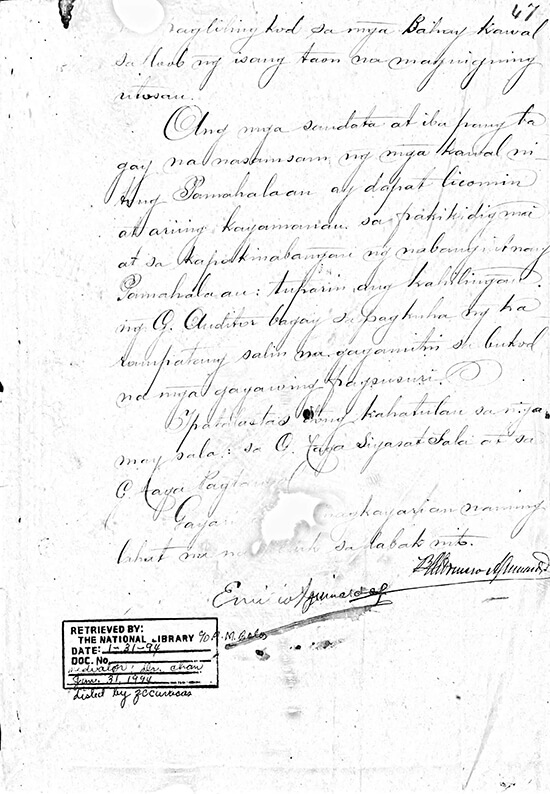

Imagine gazing on this trove: The very first book written on the Philippines, De Moluccis Insulis. (Two years ahead of Pigafetta’s more famous account.) The harrowing account of the Trial of Andres Bonifacio. For Juan Luna fans, Rizal’s handwritten toast to his bagging a gold, just like Caloy Yulo would do a century later. The page from Emilio Aguinaldo’s diary for June 12, 1898 (yes, in the days before Microsoft Outlook, he recorded that independence was declared at exactly 4:20 in the afternoon!)

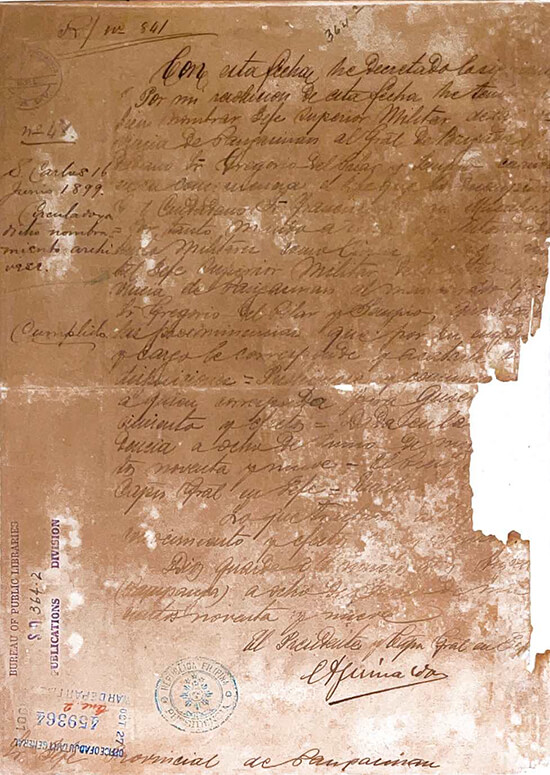

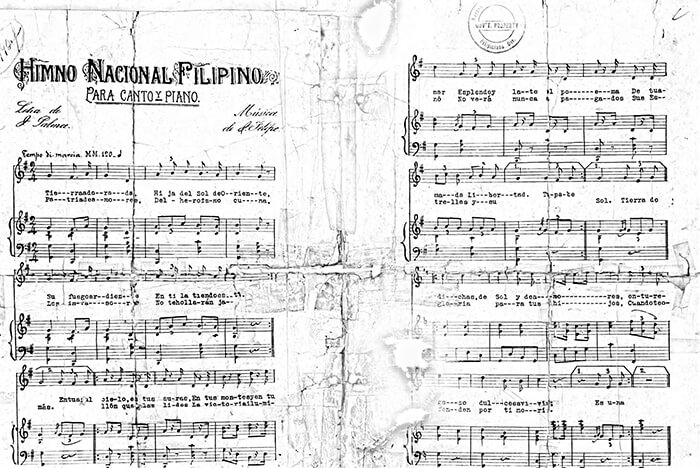

Also a must-see: his pained resignation as the first president after discovering the corruption of some of his officers. (His friends prevailed on him not to send it out.) Goyo’s appointment papers as commander. (Surprise! He wasn’t the youngest—that was Manuel Tinio of the Ilocos-based Tinio Brigade.) The musical score for the National Anthem— music by Julian Felipe but with the original words in Spanish by Jose Palma. (He happened to be the kid brother of Rafael Palma of UP’s Palma Hall.)

These are just some of the 80 books and documents that give us the inside story and the real lowdown on 400 years of Filipino history.

The Treasures of the National Library are now on permanent display and open to the public in a climate-controlled, darkened (the better to save the documents from degradation) Ali Baba’s cave of a hall. Velvety, thick black carpets give you the sensation that you’ve stepped into a jewel box. Indeed, it’s all orchestrated to make you think you are discovering these treasures for the very first time—which, technically, is exactly right because you see it at last with your own two eyes and not in a badly printed textbook.

Under the stewardship of director Cesar Adriano, our nation’s repository has been slowly but surely opening its vaults. Prior to this landmark move, these gems of our country’s past could only be viewed with the express written permission of the director.

“It’s the country’s printed wealth,” Adriano explained. “These are the books and papers that shaped our history. We want it to be a haven, for everyone rich or poor, who wants to learn more about our glorious past and our country. It’s a collection for everyone to see.”

In truth, it’s just a tiny fraction of the hundreds of thousands of documents to be found in the National Library.

Beside the gallery is a glass-enclosed pen where conservators in white lab coats toil every day to keep the rare collections in tiptop shape. (Readers with a scientific bent will enjoy the demos.)

The kernel of the idea to throw the treasures open wide began almost two years ago when First Lady Liza Araneta Marcos decided to take the Presidential Library at Malacañan to the National Library.

Nobody could actually access its precious volumes because of the Palace’s tough security measures, and it was a bold move to take the trove of heritage, culture, and law books—many of them first editions and autographed by their authors that any law student would give his eye-teeth to see—to share with students and scholars.

To be exact, 66,000 volumes were transplanted, thanks to a special loan agreement to the National Library and now thousands come daily to read and study these tomes free of charge.

As the behind-the-scenes inspiration for the enterprise, the FL was no doubt the fitting guest of honor at the opening of the new Gallery. Newly minted Secretary of Education Sonny Angara was cast in a supporting role. (He quipped that the President’s favorite subject was history.)

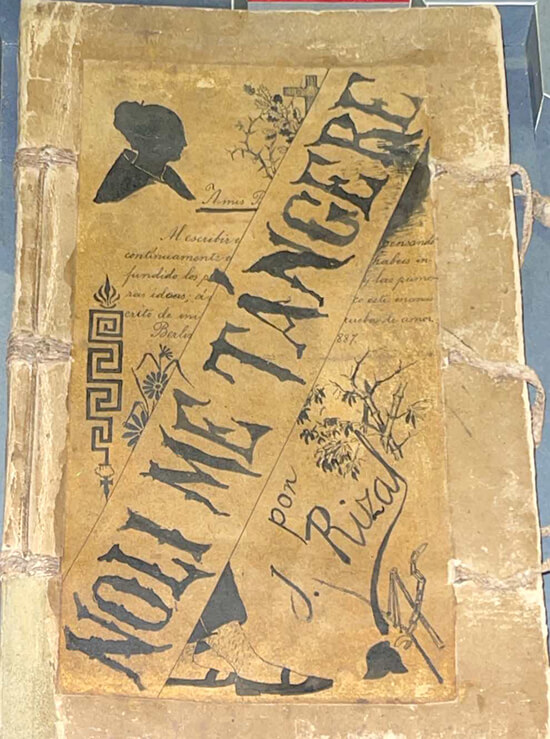

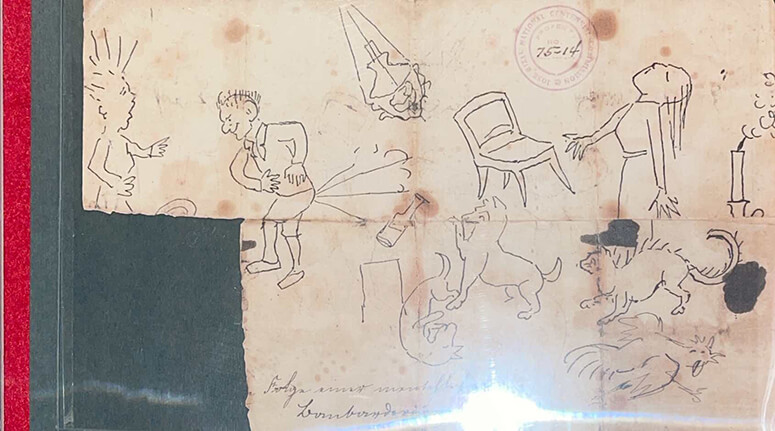

To be sure, there are the crowd pleasers and headliners such as Rizal’s handwritten manuscript of his Noli Me Tangere—and the last piece of writing he would ever do, his “Ultimo Adios” that was smuggled out of Fort Santiago in a lamp the night before his execution. Both the Noli and his last farewell would shake up the country—and the Spanish empire.

There are marvels such as the “Acta de la Proclamación de Independencia del Pueblo Filipino”—in short, our very own Declaration of Independence. (My only complaint is I would like to have seen every single sheet and all the signatures displayed under glass.)

Providing crucial context is also a never-before-seen outline of what looks like Aguinaldo’s idea of the First Republic, jotting down his supporters and which towns they controlled. (It could easily be a modern-day chart for the upcoming midterm elections.) There are Katipunan membership documents, dated as late as 1900, proof that Bonifacio’s secret society was alive and kicking despite all attempts to quell it.

There are first editions of everything, including Rizal’s own groundbreaking history book, Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas de Antonio de Morga, which gave us his view of our pre-colonial islands.

Glimpse the first Filipino novel (by Pedro Paterno and not by Rizal), and Commonwealth documents from Manuel Quezon and the inlaid desk he wrote them on.

There are front pages of newspapers reporting the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the declaration of Manila as an open city. (The Amorsolo masterpieces of the Japanese Imperial Army’s excesses are, alas, on loan to the National Museum—but that’s just a block and a quick walk away.)

The National Library was, until now, one of the country’s greatest cultural secrets. Although it occupies prime real estate (granted to it by the Rizal Park) and covers eight floors and almost two hectares of books, shelves and reading rooms, it wasn’t really on anybody’s radar. That is all set to change with this monumental first exposition.

It’s a little unsettling that less than 100 pieces of the printed word could so aptly traverse our history and our heroes—and our nation’s obsessions. But the astounding move to share at last, what Adriano calls “a carefully curated” selection of its vast holdings is as revolutionary as the documents in it. For the first time, it holds up for the public’s scrutiny an honest view of our past. There are no guardians of this portal, no interpreters or researchers. Call it history unfiltered, raw and real as it comes.

“Education comes in many forms,” declared First Lady Liza Marcos at the Gallery’s opening. “Whether hardbound or soft, online or in the newspapers.”

After all, access to our Filipino wealth in print is the beginning of any education.