The Last of Us: Love against all odds

War and distance, mothers and religion, one or the other can quickly rob men and women of that fleeting dream of happiness in each other’s arms. The idols we worship—painters, writers, and heroes—are no different and, in the end, are only mortals, their fates bound up with the same commonplace circumstances that can divide us from true love.

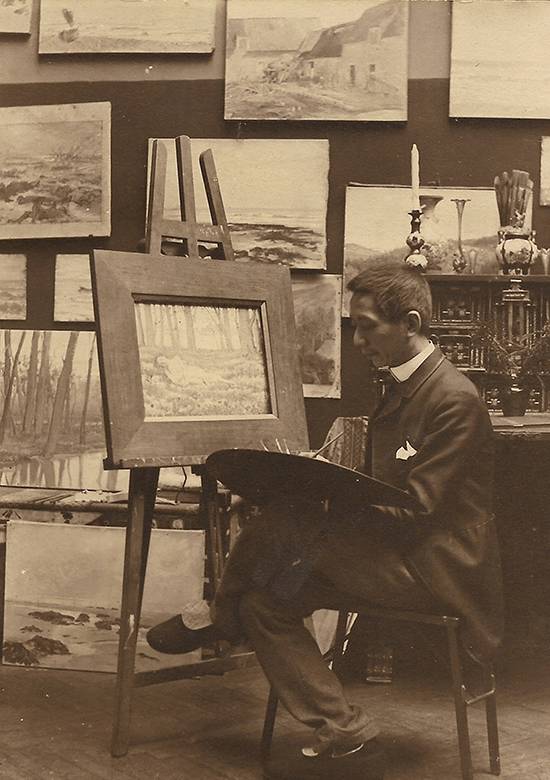

There is the case of Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo, the extraordinary 19th-century painter who, like Juan Luna, would win against the best of Spain’s painters, and Maria Yrritia, his model and companion of 40 years. It’s been written that “except for brief moments in their lives, they were attached to each other as a flower and a leaf to a stem.”

And yet Hidalgo would never marry her. There is one tantalizing episode, however, when they would come close.

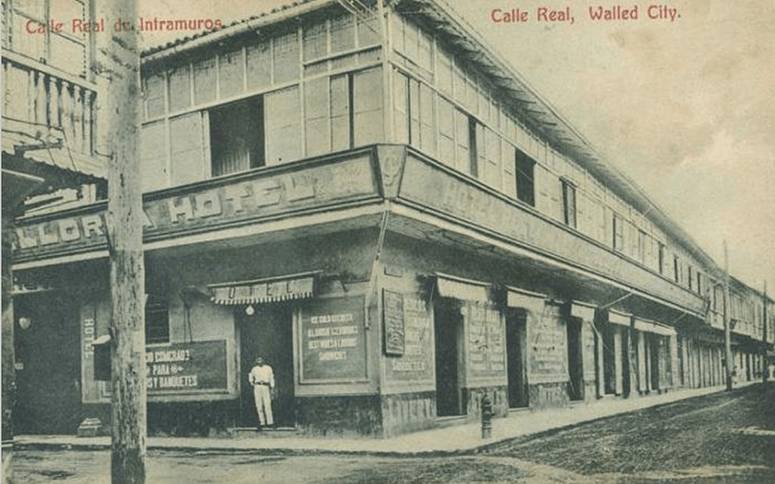

Maria appears to have “been allowed to visit his country” in 1909 and one suspects it was for the purpose of feeling her way into his mother’s approval. The mission ended in failure before it had even started and she would wind up remaining in glorious isolation in an expensive suite in the La Palma de Mallorca hotel on the Calle Real in Intramuros.

Her overtures to the family were purportedly rebuffed and she “found herself alone and hurried back home.”

A few years later, Hidalgo would be summoned by his mother, now quite sickly, but he would find Manila so impossible that he would cut short his trip and head back to Paris. Could it be that he, too, was unable to bear the grand Doña Barbara Padilla de Hidalgo’s disapproval? Alas, he would catch a chill on the Trans-Siberian Railway (read the Orient Express) and pass away unexpectedly.

Maria would make one more trip to Manila, this time to bury him, as one biographer wrote, “accompanying his body like an old, faithful slave.” This time, it was she who refused his family’s welcome and returned to France. She would belatedly have a change of heart—almost certainly beguiled by the prospect of spending her last days in the same city where Hidalgo was buried.

She boarded a boat with her collection of his paintings but would perish in a shipwreck off the coast of Africa. In one sense, Hidalgo would at last be by her side for eternity on the ocean floor.

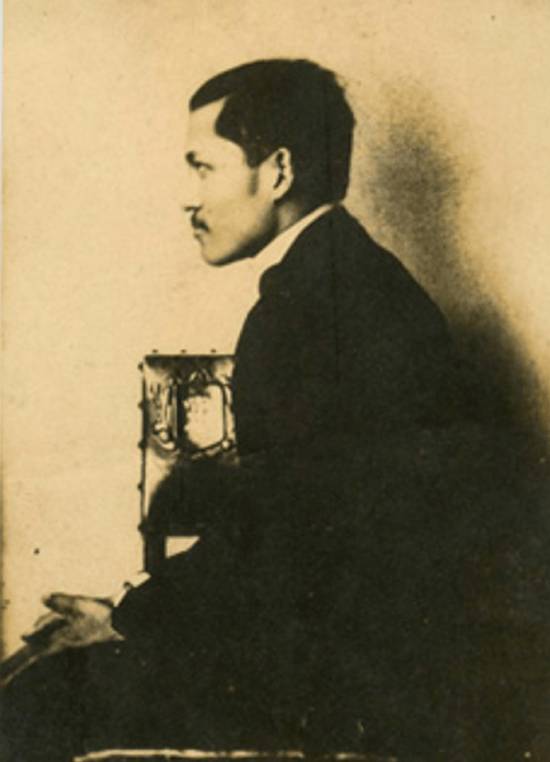

Jose Rizal would also suffer from the censure—and censorship—of his beloved’s mother. Leonor Rivera’s would famously intercept his letters, leading the girl to believe that she had been forgotten.

Her mother was convinced, not without reason, that her daughter would be far better off marrying a British expat than a troublemaking writer, a truism still held dear by maters to this day and age.

Leonor would eventually discover her mother’s machinations and would be allowed only to keep the letters if she agreed to burn them to ashes. She would leave instructions that the charred remains be sewn into the hem of the dress in which she would be buried.

The pain and peril of marrying a freedom-fighter was often too much for an ordinary woman to bear. Not so in the case of Gregoria de Jesus and Andres Bonifacio, who is said to have fallen in love the minute he laid eyes on her, dressed as Reina Elena, in a mayday procession.

She would lose the man known as “the Supremo,” cut down in the foothills of Maragondon, which she scoured in the rain and mud to find his body.

Less than 50 years later, Lyd Villanueva would lose her husband, Manuel Arguilla, a short-story writer turned guerrilla fighter, to a Japanese firing squad. She would go on to found the Philippine Art Gallery, the country’s first devoted to the cause of modern art that nurtured the likes of Anita Magsaysay-Ho, Ang Kiukok and Vicente Manansala.

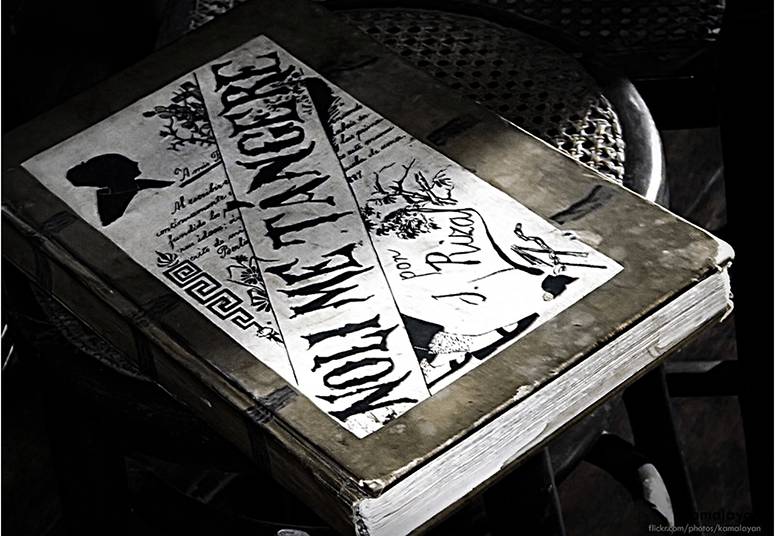

Rizal would conjure in the Noli Me Tangere the most tragic love of his novels, that of the crocodile-hunter Elias and Salome of the lake. In a heartrending parting scene, Salome beseeches him to stay in her home even when she has left it so that she may imagine that they are still together when she closes her eyes at night.

One wonders what her fate would have been since he had given her the same name as the temptress who would ask for John the Baptist’s head. Nobody will ever know since Rizal would strike out the entire chapter detailing their love affair when it came time to print the book, dooming them a second time. (A very rare painting by Fernando Amorsolo of the star-crossed lovers is featured at the León Gallery Asian Cultural Council auction this Feb. 18.)

When Rizal did fall in love again a decade later it was with the mestiza heiress Nelly Bousted. His hopes, however, would be dashed once more by her devotion to a different religion.

In the summer of 1891, she would write him from the familly’s Villa Eliada in the aristocratic resort-town of Biarritz, in an impatient, accusatory tone a guilty man will recognize: “When (my parents) wanted to know what my feelings towards you were, I told them that I could not express them before knowing whether you had embraced Christianity.”

Things had apparently progressed enough for her to be able to rebuke him: “I want to wait willingly for some time so that you might study the case with calmness and in solitude without making haste; and on the other hand, because I have promised you fidelity… to think that I have made of you a simple (toy), you do not understand me!”

With finality, she adds, “If you could only be more disposed to hear the voice of Him who asks your heart and your service, that would be better for two reasons. For you and for us.”

Rizal would refuse to believe in the dream and sometimes that is the final and worst obstacle of all.