Miguel Syjuco & the ongoing war over who will tell the stories the world will know as true

When we aspiring writers were slouching toward Dumaguete’s Boulevard of Broken Dreams on one of those heady evenings in 1998 — half drunk, smelling of some fragrant fiber, listening to a Siliman National Writers Workshop co-fellow murder her own ballad — we knew right away who would go on and make it in the literary scene. While I would find myself getting canned for refusing to write news about copra in a business daily, Carlomar Daoana and Lawrence Ypil would create stellar careers in the literary scene. Those guys were forces of nature. Like Ja Morant or Luka Dončić with illumination and free verse — my jaw left hanging with the fluidity of their expression, how oracular their imagery was. Same with one Miguel “Chuck” Syjuco.

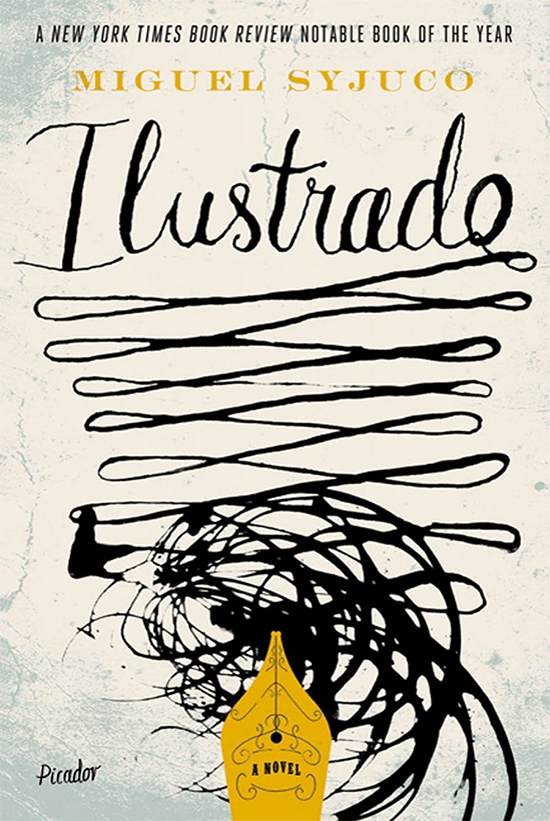

As Krip Yuson provides a masterly examination of Syjuco’s follow up to the award-winning Ilustrado, we catch up with our long-ago Dumaguete drinking buddy, who claims he is currently “nowhere and everywhere,” “totally offline” and existing only “on the page.”

We ask Syjuco whether a fictionist still has a place in this world populated by the Gazpacho Police, Jewish Space Lasers, and raiders of the lost Tallano Gold. Or what would be probably doing on May 10, 2022 — the day after the Philippine Presidential elections.

He answers, “Weeping — for sadness or joy, it remains to be seen.”

THE PHILIPPINE STAR: After your award-winning Ilustrado, was there tremendous pressure thrusted upon you in writing your next book?

MIGUEL SYJUCO: As a writer, there’s always pressure, from within and without. Breadwinning, mercurial ego, hectoring id, fickle superego, endless stream of smartphone messages, the quotidian demands of addictions and loved ones, the nourishing distractions of people’s needful requests, and, of course, the infinite possibilities of the novelistic form — all part and parcel of a novelist by trade.

But what threw me for a loop, beyond my tendency for bad decisions, was grappling with the question of a novel’s purpose. Words, clearly, are powerful, enough for despots to try to control what we can say and write. Stories, obviously, are essential, as the stuff of our identities, beliefs, and aspirations. But can a novel change this world that clearly needs changing for the better?

Beyond literary fiction’s role in weaving society’s narrative as connective tissue, and distilling language in delicious new ways, and instilling empathy for the complexity of individual human experiences, what else can a novel do? Does it simply entertain on languid vacay in Bora? Or comfort in bed and encourage sweet dreams? Or can a novel challenge readers into action, the way some works of fiction in history have done? — each proving the potential potency of any well-meaning, inspired, dogged human being at a desk stubbornly building a story they feel is vital enough to deserve telling. After all, there have been novels that helped abolish slavery, overthrow conquerors, or stand against tyranny.

So I felt, as a novelist, the pressure we, as citizens, all feel: to do something, with the tools we’re most skilled at, in this world of urgent problems. For now, my offering is I Was the President’s Mistress!! Because I believe in literature. What’s more, I believe in readers. And to them, this novel will be challenging, in all senses of that word.

What was the spark of inspiration for I Was The President’s Mistress!! Was there a particular line, an incident or story arc that got the ball rolling?

Our protagonist, Vita Nova, was the most maligned and misunderstood character in Ilustrado — forever in the background, discussed by others only through rumor and misconception. So I wanted to proffer, in this sequel, the space to tell her side. In her own voice. In contrast to the stories society sought to impose on her.

And as I did my research, to write her as responsibly as I could, I found in Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Second a reminder and a guide — “On ne naît pas femme: on le devient.” One is not born woman, but becomes one. This became central to how I approached this character, who I feel is the most complex I’ve written yet.

Because although I believe that artists can and should inhabit any and all roles — to learn different perspectives and develop our art — my limitations and privilege as a male writer weighed heavily on my skills that were still developing. Over 14 years, and at least as many drafts, I came to examine, critically, that male gaze, as well as the convolutions of how we perceive each other, and how such perspectives can conflict as they vie in our minds to become the truth.

Vita, with her apparent masks, which she uses as tools and defenses, is both bida and contrabida, in a society that loves facile dichotomies, and where such roles come with preconceptions and the implicit weight of judgment.

But we all know real life’s more complicated than that. Those complications are what I Was the President’s Mistress!! is, largely, about.

How would you describe your process of writing? Is it a torturous one? Or sentences and paragraphs simply gush? Describe your writing desk.

Writing is, I often feel, the hardest thing — and if it isn’t you’re not pushing yourself to reach further. Anyone thinking otherwise should try writing a novel, then try making it good, then try to getting it published. It’s painful, arduous, and there’s a million things I’d rather be doing, like taking photos, or working with an NGO, or building something with my hands. Once writing became my profession it lost much of its joy — which I strive to find again, via the insane solution of, yes, writing more. And when you consider how a novel takes years, with no guarantee of publication, one can only see it truly: as madness.

But it’s also what I’m best at, I think. And I’ve worked hard to establish myself as a novelist of literary fiction. And its potential for good is immense, privately and publicly, if I can get it right. If I can get more and more readers to take the challenge of reading in new ways, of discussing difficult ideas, and of answering thorny questions by taking action.

My desk has the mess of someone kicking and screaming to not be there. Stacked with the detritus of a literary life — books, papers, totems, writing instruments — which I’d tidy up if only it didn’t mean time away from writing. In other words: objects that stand as metaphors for the temptations of procrastination, distraction, and a mind too cluttered. But smack amidst the chaos stands a battered, hot laptop and a maniacal resolve to write the goddamn book I want to get written, and to get it right, even if it means years of planning, outlining, sketching characters, drafting, revising, drafting, revising, drafting, revising, then throwing most of it away to start rewriting — following the advice of Samuel Beckett, that master absurdist: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

What’s a typical day for you? (Aside from getting daily accolades from the likes of Salman Rushdie, whoosh.)

I thrive on ritual, by necessity, to carve out the space I need to write. My years of doing parkour has this motto singed into me: Être fort pour être utile — Be strong to be useful. So I do yoga or stretch, thread mindfulness into my ablutions, slurp granola and berries, and only then pick up my mobile phone to check what’s new in the world — which is always a mistake, with all those endorphin-injecting messages awaiting my replies, followed by the flow of news scrolling, from which I finally tear myself away, disgusted that today, again, I haven’t learned my lesson. Then I finally buckle down to doing every other pressing task that isn’t my writing.

Only after I push all that aside, or if a deadline brandishes its sharp edges, only then do I sit my groaning lumbar at my writing desk. By that point, my inertia ruptured, I desperately cling to the task for hours, past the setting sun, late into the night enough to threaten the productivity of morning tomorrow.

Fortunately, that’s only pretty much each weekend and every holiday. Weekdays I’ve got my teaching job that I love to hate because I should be writing, but which at least allows me some human interaction, some tangible rewards, some wind while on a skateboard, some sweating outside, some TV binging, some time in a book that’s not my own, some love and affection. In other words, some normalcy — weighted with guilt slash frustration that I’m not writing.

Do you plot or outline your novels? Maybe similar to how movie detectives track serial killers on a whiteboard or that meme from It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia?

Because I’m obsessed with structure, and making the reader more complicit in the narrative, I plan what I’m building as if I were an architect. I make blueprints, create models, erect scaffolding, and sketch out schematics for every component and level of the book. I’m deliberate in my craft choices, knowing that each offers particular narrative uses while limiting certain other effects.

Ilustrado was my apprenticeship, where I learned all those tools available to a novelist — which made the book symphonic in its use of diverse narrative components. In I Was the President’s Mistress!!, I focused further on voice, structure, character, unreliable first-person perspectives, revelations that must be read between the lines, and fluidity of temporal tense — all to create movement, as an experiment to eschew narrative reliance on plot. And because I wanted to write a book of ideas, in which the reader must decide for themselves, and reaffirm their own values and beliefs, I had to plan carefully how I’d weave those goals into literary mechanisms that conventionally pull a reader along in a book.

To me, a novel is a theory — of the form and of the world the narrative portrays. And given all this book’s moving parts, I needed to sketch things out beforehand. Sometimes I think it didn’t help, given how many times I rewrote it almost from scratch. But then again, it’s finally done, this beast that I’m glad to now send off for other people to wrestle with. To them I wish godspeed and coraggio.

What can you say about the state of the world right now: after a Plague, War… can Pestilence be far behind?

The pestilence is already here: that of disinformation, misinformation, false narratives, and perverted history.

All of which, to my mind, have flourished as we private citizens have so willingly ceded our right to privacy — via our social media feeds and constant connectivity — while our public servants have built their walls of privacy ever higher — hiding their use of taxpayer funds, their medical fitness, their statements of assets, liabilities, and net worth.

To our right, as private citizens, to publicly judge their fitness to lead us, they dance with glee around transparency and accountability now that they can dictate what’s taken as truth—so much so that facts no longer seem to threaten them. The proverbial guns, goons, and gold they once needed to keep power seem much less important than savvy, money, and technology.

As we’ve let our lives become fungible content, and our individual data be sold, the facts of our existence have become all the more easily manipulated. And while the masters of this pestilence of untruth so easily pit us against each other, the stories we used to share about who we are as a society, and what we could achieve together, now seem like pipe dreams.

How significant is the role of the novelist in today’s world of alternative facts, fake news and revised histories? How significant is the role of the Filipino writer today?

More significant than ever. From journalists to civil society fighting red-tagging and nanlaban shrugging, to netizens defiantly vocal against troll mobs and weaponized laws, to artists pushing boundaries to protect the right to free expression from being more tightly corseted — all of us play an integral role in safeguarding the facts of the past, seeking the verities of our present, and defining the possibilities for our country’s future. All that’s more important than ever, now, in this ongoing war over who will tell the stories the world will know as true.

What can be done to encourage more Pinoys to read our very own literary output?

Write bravely. Read assiduously. Translate relentlessly. Celebrate each other’s voices. Do everything you need to craft your stories. And don’t ever give up.

Let me be the devil’s advocate: why write long, labyrinthine novels when people’s attention spans last as long as a TikTok post?

Why? As George Mallory replied in 1924 to the question of why attempt to summit Everest: “Because it’s there.”

And precisely because our attention spans today last as long as a TikTok post.

Some readers love, as I do, the journey of a big, challenging novel — the kind that forces you to participate beyond voyeuristic passivity or emotional feels. Books that involve you as an accomplice rather than a consumer. I respect all readers and I believe there are enough out there who feel the same as I do.

But long, labyrinthine novels require timing, awareness, readiness. When you read Joyce, or Cervantes, or Austen, or De Beauvoir, (or Richardson, or Rand, or Elliot, or Wollstonecraft Shelley...) you prepare yourself to read them — blocking out time and space from your life to commit to the whole voyage, enduring whatever imperfections, anachronisms, or swampy bits because you trust that in the end the shared effort — of both writer and reader — is worthwhile.

I’d like to believe that my novels are worthwhile. Perhaps particularly because I don’t write to be marketable or so-called accessible. I know that some readers blame me for not engaging them enough, but I’m not here to pander, or entertain, or hand-hold, or presume that any reader is less than me. I read a lot, so I write the kind of books that I wish existed — that I would like to read. If you don’t like my work, that’s okay. Maybe this particular book’s not for you right now.

There are enough people who tell me they enjoy my work; it’s for them that I write it.

What is the best line written in all of English literature?

“Jesus wept.” The shortest verse in many versions of the Bible, but the pithiest — the subject of endless interpretation; its usage now both sacred and profane: with its liturgical significance versus its colloquial subversion (like ’Sus in Pilipino, or tabarnak in Quebecois). Most of all, it exemplifies to me the use of silence as an essential tool in writing, to tell the larger story that must be read between the lines, beyond the exposition — silence as the invisible prose of a narrative; silence as the ultimate poetry — which invites, and demands, the active agency of the reader’s imagination and conscience. In the white space beyond the black ink, the story must be told by you, yourself, about our shared humanity. “Jesus wept” narrates the immense story of his mortality; but the way we readers can expand and act on the briefest of words only proves our universal divinity.

What is the worst?

“...he thought to himself” / “...she thought to herself.” My biggest pet peeve. Because who else can you think to?

What books changed your life?

JRR Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy got me reading as a child. Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote taught me the imaginative possibilities of the novel. Jose Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere taught me the social possibilities of fiction. Alain Robbe-Grillet’s Jealousy revolutionized my understanding of narrative perspective and reader involvement. Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire and Jorge Luis Borges’s short stories taught me the intellectual provocations of narrative play. Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises taught me the use of inference via silence. Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint taught me energy, flow, and structure. Then Virgina Woolf’s To the Lighthouse taught me how ignorant I’d been by inadvertently reading only novels by men — which I’ve spent many years now working to resolve, to my great enlightenment.

“Where books are burned…” What can you say about the predilection of white supremacists in the US to ban or burn books?

What can I say about those poster children for abortion? Those book-burning racists who cry “cancel culture!” when communities or private companies censure them? Those f*cktards who cannot understand that the First Amendment only guarantees that the government cannot seek to abridge freedom of speech — and that free speech doesn’t protect their public statements from criticism or social consequences? You mean those same people whose hate speech and burning of books is protected by the same US Constitution that ensures those books can be published?

I could say about them whatever the hell I want — thanks to our universal human right of free speech. Which, although suppressed in too many countries, is constitutionally protected in both the US and ours.

But I’ll offer instead that handy summation of Voltaire’s belief: “I disapprove of what you say but I will defend to the death your right to say it.”

Who among these writers got it right: George Orwell, Margaret Atwood or Rod Serling? Which book or books have you read that today sounds eerily prophetic?

All of the above. Orwell, about what the world’s become today. Atwood, about where we’re headed if we’re not careful. Serling, about the dark corners of our souls that brought us to this surreal current moment.

But let’s not forget Kafka, who was right about our institutions grown blind to their service to us as human beings. I was reading The Trial recently, which reminded me of academia, of government, of our societies’ institutions justifying their incompetence in the face of problems like climate change, disinformation, eroding democracy, and rising authoritarianism. Kafka wasn’t just a writer, he was a prophet.

What can you say about the rise of autocrats and fascists in the Philippines and the United States? Should we be mildly concerned like Susan Collins, alarmed like Twitter doomsayers, or is it simply the time to abandon ye all hope?

If the stain of Trump, the impunity of Duterte, the return of the Marcoses, the mass brainwashing of China, and the invasion of Ukraine by Putin and those he controls aren’t reason enough to be alarmed about humanity’s ability to address eroding truth and rising sea levels — then I don’t know what is.

Since you asked me: We should all be alarmed into action before we lose all hope.

Was there pushback from the administration when you wrote those scathing op-eds in the New York Times?

If you mean the relentless troll mobs, death threats, mocking memes, character assassinations, and attempts by the administration’s proxy Duterte Disinformation Squads to dox and cancel me — then yes, I’d say there was pushback.

The thing about my op-eds in the NY Times and elsewhere was that they represented opinion informed by what I’d gone to see firsthand in the streets — at crime scenes, morgues, wakes of EJK victims, mass burials, jails and rehab facilities, protests, and interviews with politicians, police generals, human rights lawyers, civil society advocates, and, most importantly, residents of terrified communities.

So I wrote about our broken justice system that our law-and-order president didn’t really bother to reform. I wrote about communities struggling to fix our anti-drug government’s failure to help Filipinos locked in addiction. And I wrote about the bloodshed that the regime and its opportunistic sycophants tried to spin as good for our country.

Of course such NY Times pieces were scathing — I’d actually witnessed what the bloggers had been willfully blind to in their potemkin portrayal of the Philippines under Duterte.

With I Was the President’s Mistress!! there’ll probably be further pushback, as you call it, even though my new novel is wholly, absolutely, entirely fiction based on nobody at all, though inspired by a country where truth is stranger than fiction. You can imagine what I’ll receive: the lies, exaggerations, deepfakes, facile tu quoque fallacies, and ad hominem attacks coming for me as a private citizen simply exercising my right to call out our feckless public servants and their paid minions. You can already imagine the embittered slurs: burgis, out of touch, lying, drug-using, philandering, hypocritical coño kid who has written something that offends them and must be cancelled using our much-abused criminalized libel laws. Hay naku — been there, done that; they’re so predictable.

If you don’t like my work, don’t read it.

How can you describe Philippine society, which has seemingly forgotten the lesson of history? Are we (the rest of us who have not gone amnesiac) doomed to repeat all that shit?

Too many of us continue to be fooled by the professional propagandists and disinformation mobs funded by what I can only assume are the billions stolen from us Filipinos over two decades of a dictatorial regime. The facts and truths of history are being warped on behalf of kleptocratic politicians who have for generations shirked blame and responsibility — refusing, as always, to stand and face the scrutiny of what remains of our free press or any attempts at healthy debate.

But who can blame foolish voters for being beguiled by freshened-up old lies and a relatable fantasy of victimhood and potential greatness? Especially after 36 years of rulers who failed to use that fresh start of 1986 to build a society that could grow sufficiently beyond patronage politics, impunity, inequity, lack of education and opportunity, and the dictatorship of dynasties that thrives till today.

I believe the fresher traumas and disappointments of the last three decades have, unfortunately, obscured the catastrophes of the dictatorship. Meanwhile, the authoritarian efforts of this recent administration stabbed a kris in the struggling heart of our faith in democracy. Because make no mistake: it is not democracy that could lead little Marcos Junior into the Presidency; it’s the hijacking of a system so broken that we could only watch the steady gutting of it these past six years.

It’s unfortunate that the more information we have at our fingertips, the more batshit people have become. What can you say about the conspiracy theorists and red-taggers in the US Congress and Philippine government? Can any piece of literature (Tom Robbins, Thomas Pynchon) compete with all the crazy pronouncements they make? Jewish Space Lasers and Pizza Pedophile Ring, anyone?

Ours is a country where the truth is stranger than fiction. Where the Al Qaeda plotters and Cambridge Analytica manipulators of the world experimented and refined methods used to attack America as a key example of democracy. In such ways unimaginable, we have the proud honor of being first — just like we’re the first in being last in all those COVID resilience rankings.

Clearly, we Pinoys need no Jewish space lasers or pedophile ring in the basement of a pizza parlor, not when we’ve got the guiltless greatness of the Marcoses, the benevolent utilitarianism of the Dutertes, the record-breaking bodycount of the Ampatuans, or freedom for child rapist Romeo Jalosjos. In the immortal words of Hunter S. Thompson: When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro. And in the Philippines, they seize power and never let go.