Can’t spell Jakarta without ‘art’

When it comes to art fairs, there’s always a delicate balance—more so in Southeast Asia, it seems—between fostering creative talent from below and stoking commerce juices from above. The trick is to hit that magic combination: an art fair that has global buzz and local grit.

For this year’s Art Jakarta, which ran from Nov.17 to 19 at JIEXPO Kemayoran, the attention was on cementing the fair’s return after a long pandemic with stronger corporate presence.

Fair director Tom Tandio lauded the expansive 10,000 sqm. space spread across two larger exhibit halls of JIEXPO, offering a more logical flow than the Jakarta Convention Centre.

“The move to this larger space allows us to engage with bigger installation works and more collaborations,” he said in his opening remarks on Nov. 17. “We believe this year’s edition could exceed visitors’ expectations. Also, more foreign collectors are coming since it is the fourth quarter of the year, a more fortuitous season compared to our previous schedule during a summer month.” The fair was originally planned for Oct. 4.

Showcasing 68 galleries—up from 62 last year, with 40 from Indonesia and the rest from Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam, Taiwan, South Korea, China, Japan, Russia, and Australia—the increase may seem modest, but to Tandio, it’s just the right fit. “For Indonesia, I think a good size is 70 galleries. Beyond that, it only makes the fair look bigger, but it isn’t good for everyone. It depends on the market. Can the market accept it? Can the market buy enough to be satisfied?”

This time, the three main partners—all finance-related—were global wealth management leader and art patron Julius Baer; regional banking institution and arts supporter UOB Indonesia; and digital investment application Bibit, which brought in Indonesian artist Syagini Ratna Wulan’s installation Memory Mirror Palace from Venice Biennale 2019 to exhibit before local crowds.

I asked Tandio if Indonesian art could exist at this big a stage without corporate sponsorships. “Of course, artists can always produce artwork, but sometimes being shown in a place like an art fair—which we know is the most expensive place—these corporations really do help.” He noted that prime space in two JIExpo Halls was devoted to corporate-developed projects—not just product placement. “If you look at all our partners, almost zero of them do like a product booth; all of them are art projects. Even Mini Cooper and Julius Baer sponsored new art projects.”

Amid art gallery booths both cutting-edge and pop-oriented, there was Julius Baer exhibiting winners of the Julius Baer Next Generation Art Prize in Asia 2023, presented in a special area: the Julius Baer VIP Lounge (with Johnnie Walker sips for VIPS).

There was gold-trading app Treasury, holding a champagne launch of its 2023 Art Prize winner Eldwin Pradipta’s video work, Is This ‘Art Work’ in the Room with Us Right Now?, examining the source of the gold standard (long story: starts with King Croesus) and once again questions the existential “value” of a soft metal that, nonetheless, remains highly sought in most circles.

There was the special BMW section devoted to a Jeff Koons souped-up pop art model; and a grass-laden Mini Cooper (designed by Indonesian artist Syaiful Garibaldi) that speaks of the harmony of nature, camouflage, and a sort of herbaceous luxury.

All these VIP-servicing tweaks do not detract from a bigger focus: allowing a series of special exhibits to hold center stage within each of the JIExpo Halls.

The UOB Art Space exhibited 25 new artworks from Southeast Asia UOB Painting of the Year competition from Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Balinese artist Ni Nyoman Sani won first prize with her abstract work Tranquility, embedded with tiny dead corral fragments arranged in undulating patterns; it will eventually be displayed at UOB headquarters.

Meanwhile, local music and sports event giant Superlive exhibited three electric guitars (Supermusic-Superstar) splashed with prize-winning art designs, a testament to artists rising up from adversity.

AJX presented Vice Versa, a book/art project initiated by Indra Leonardi, who photographed 78 Indonesian artists, and then had them further artify the images. The final portraits are doubly striking.

And finance app Bibit devoted a large floor space to Wulan’s immersive display Memory Mirror Palace, with its connected labyrinth of 178 mirrored glass boxes, each containing an enigmatic object and bearing curious phrases such as “CHOOSING SIDES FOR THE REST OF HUMANITY” or “WHERE WILL I BE WHEN I REACH THE CONTEMPORARY?” The phrases are loosely connected, and the artist’s work points to the endless splintering of our everyday choices—something like the multiverse making each decision a possible branching into infinitely more choices. (A Bibit rep explained that this somehow ties in with the app’s focus on the importance of each investment choice, though I choose to think the work exists on a somewhat deeper level.)

On the pop side of things, there was Museum of Toys’ focus on overblown pop figures that look playful and almost edible, or the mammoth, Botero-like pop sculptures of Adi Gunawan (this is an artist who found little market for his figures while they were thin, but gained a huge audience when he began rendering them plump and serene). Personally, I found more intriguing the display of Vinautism Gallery, whose owner Rudy Purwono features work created by autistic artists, including his own son Vince (the work is therapeutic, draws him out, stimulates his interest—in this case, trains); or the work of “shamanistic artist” Sherry Winata at an adjacent booth, whose paintings combine meditation and abstract painting in her path to spiritual growth.

In a largely Muslim country, I counted only a single piece that addressed the Palestinian situation, albeit the small panel by Taipei artist Wu Chia-Yun was likely created before the current Gaza situation. It’s an image overlaid with this haiku-like statement: “The Palestinian driver heard I’m from Taiwan/He got very excited/and said to me/Be strong, together/At that moment/I didn’t realize what he meant.”

Then there was Indonesia’s ROH Projects which, in its mischievous way, offered an enigmatic, heartbreaking installation—a selection of sneakers propped on mall-type wall racks and set atop makeshift cardboard boxes. On closer inspection the shoes are hideously misshapen and sloppily handmade—perhaps a commentary on the grotesquerie of using cheap Asian labor to manufacture our leisure kicks. Typically, not a single scrap of information was shared about its creator or intention. You are left to discuss and marvel.

Vertical dreaming

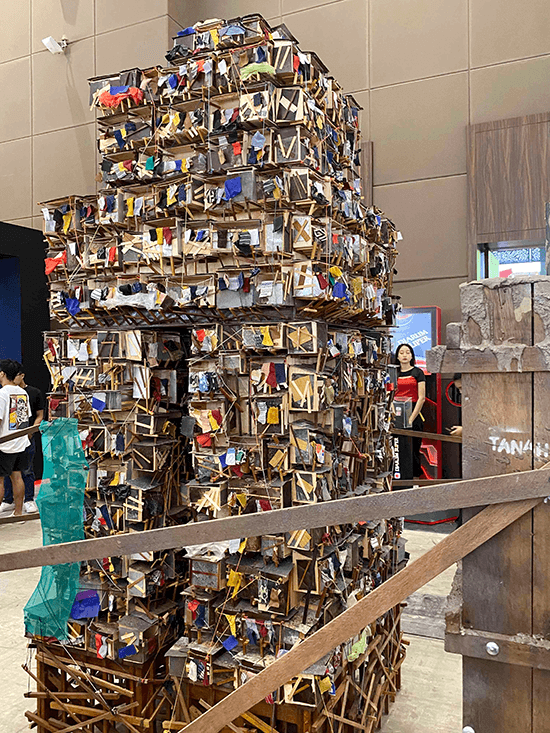

Quite a number of artists this year used vertical integration in the city as a metaphor for aspiration, or desperation. There’s the concrete pillar topped with a blue palm tree of Eko Nugroho’s Under the Tree installation, hinting at the new forced environment of the urban dweller: “nature” reduced to a fake plastic tree, while we dwindle and endure beneath it. There were the stacked squatter dwellings created by Indonesian artist Asmoadji (Bertahan Melihat Sekitar), almost parodying the idea of “high-rise living” among the dispossessed. There was the monolithic tower of Korea’s Park Jihyun, repurposing discarded domasung sheet metal fragments as a metaphor for “lost” objects journeying towards a new life.

Then there was Filipino artist Jose Santos III’s Order of Things, a pair of ascending tower constructions that hint at the cramped reality of living in a city like Manila, while integrating one’s surrounding “found” environment into a new story, here divided between twin narratives: the body, and transportation. The first pillar includes windows loaded with tiny doll faces, human figures on chessboards, along with phantom white limbs emerging from the upper reaches of his tower; the second includes rusty-looking stairs, street signs, old notebooks in nooks, deadbolts and other ephemera.

“I was reflecting on the way our environment impacts on us, living in Manila,” says Santos. And sure enough, the installation bears so many recognizable Filipino stamps—MRT destinations and silvery horses taken from jeepney hoods and push doorbells, as well as discarded face masks and other accouterments of the finite body—that you, for a moment, almost feel as though you’re home again.

* * *

Art Jakarta continues until Nov. 19 at JIEXPO Kemayoran, Central Jakarta. Visit artjakata.com for tickets and information on exhibits.