From Magsaysay-Ho to Madame X

Anita Magsaysay-Ho has made headlines for the last 70-plus years, ever since she became the first woman to be declared the best artist in the country by the all-powerful Art Association of the Philippines, the country’s first guild of painters and sculptors. The AAP, incidentally, was founded, not by a man, but by another formidable female, Purita Kalaw Ledesma, as her way of making sense of the incomprehensible, the devastation of Manila in World War II. She set up shop, like a hardy bloom among the ruins, in the pockmarked remains of the National Museum in 1948.

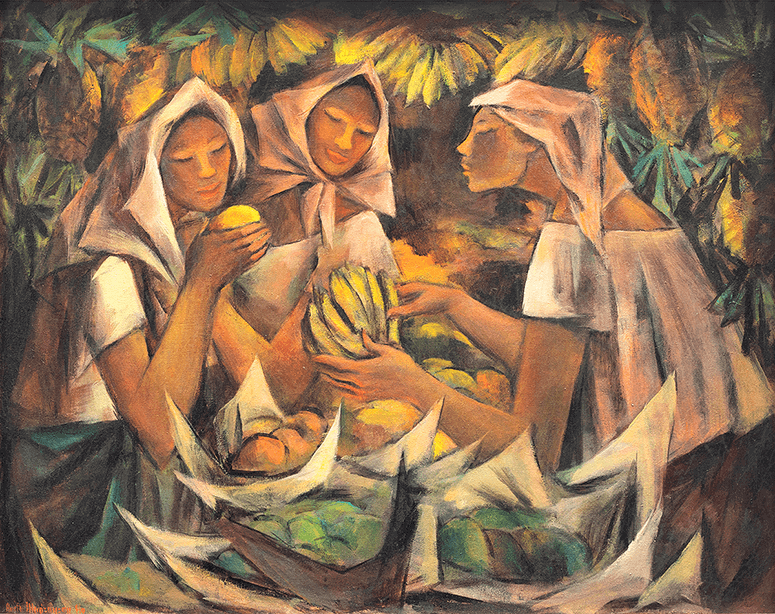

Besting a tribe that included the patrician Fernando Zóbel and the proletariat Hernando R. Ocampo, Magsaysay-Ho’s win was a sensational triumph for women in the arts. The painting that would establish her reputation was titled simply The Cooks and depicted a bevy of women stirring up a rich chicken soup. It would pave the way for Anita to capture the Filipino female at what she does best—deftly combining hard work with the tending of hearth and home—in canvas after canvas.

One such artwork, this time titled Fruit Market, was one of those gems. Not unsurprisingly, it would go on to break yet another world record for the artist at the León Gallery Asian Cultural Council Auction last February. Opening at a starting price of P22 million, bidding breezily leapfrogged to the sum of P86 million. (This was just a tad above the previous, eye-watering record for another picture by Magsaysay-Ho, Tinapa Vendors, which fetched P84 million.)

Fruit Market once belonged to one of the country’s first certifiable expat millionaires of the 1950s: the American Anderson family. Frank Anderson had founded Basilan Lumber after the War, capitalizing it for P2 million, already a vast amount for its time in the mid-century. It was his wife Betty, however, who would make their encampment on the edge of the Sulu archipelago an oasis of cocktails in cut-glass tumblers, lawn parties, and shopping for corals and lush pineapples and bananas in the seaside markets. (We know this because of a photo essay in Life magazine at the time about their elegant home in the south.) It’s no wonder that this particular painting of women at work would have such resonance with the unsinkable Mrs. Anderson.

It was acquired at the Philippine Art Gallery, already a landmark in those days for championing the curious cause of modern art in the country. The PAG was established by a group of newspaper women led by the indefatigable Lyd Arguilla at more or less the same time as Anita’s anointment. Lyd was a guerrilla fighter and widow of the prodigy Manuel who had been tortured and executed by the Japanese for being in the Filipino resistance. She would become the country’s first official gallerist and would alternately cosset and hector, and singlehandedly marshal the magnificent talents of the men who would be known as the “Neo-Realists.”

One of these men included Vicente Manansala who would, according to an interview of the time, fix on a theme and find every possible way to explore and express it. Manansala would become famous in his own right for a piece titled Madonna of the Slums, combining the purity of a mother and child with the desperate chaos of the Manila barong-barong or the makeshift hovels that had sprung up all over the war-torn city. It was a completely original idea. At the León Gallery auction, one of these elusive Madonnas would make an appearance, this time fashioned out of Manansala’s own aluminum paint tubes and streaked with the bold quadrants that would evolve into his own highly recognizable style called “transparent cubism.” This particular masterpiece, incidentally, was discovered in the dusty attic of the home of Senator Leticia Ramos Shahani, a pioneering feminist, ambassadress, and one of the architects of the law that created the National Commission for Culture and the Arts—as well as the Philippine Commission on Women. (The mid-century mater reeled in, by the by, P4 million.)

On the opposite end of the spectrum was a portrait of the colorful Maria Castro Espinosa, whose real identity was diplomatically camouflaged in Manila society by the appellation Madame X. Espinosa amassed an enormous fortune during the Second World War and it is no secret that she would acquire properties from the most illustrious families in the country who had fallen on hard times in those dark days. (One of those stately homes was a gorgeous villa designed by Juan Luna’s son, Andres Luna de San Pedro, and owned by the Zóbel de Ayala family.) The Amorsolo portrait represents a sweetly innocent young woman dressed in traditional Filipino traje de mestiza. The only hint of her mysterious prosperity is a star-shaped diamond pendant around her neck and the date on the painting of 1943, a year when the country was bowed under the Japanese heel.

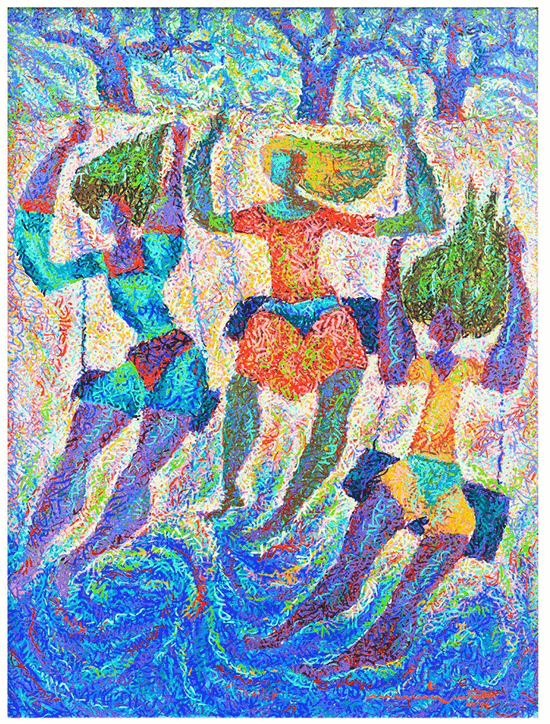

Women collectors dominated the auction scene as well: There was justifiable excitement over the sale of a mural-sized Jose Joya donated by the high-powered construction magnate Alice Eduardo. (That work titled Love Rite reeled in P60 million.) There were other works owned by famous females including Loida Nicolas Lewis and Olivia Yao: Ms. Lewis’ Flight of Angels by Manuel Rodriguez Sr. was a wonderful portrait of three young women on swings, straight out of her Manhattan triplex where it would have shared wall space with Picassos and Monets. She was one of the first Filipinas to pass the American bar and would ably steer her husband’s empire founded on Beatrice Foods after his demise. Ms. Yao’s Composition Red was by another Philippine Art Gallery stalwart who would follow her art to Paris, on the wings of a promising career in Manila. Would she have been another Magsaysay-Ho if she had decided to stay at home? Nevertheless, this rare Saguil reeled in a most respectable P6.5 million.

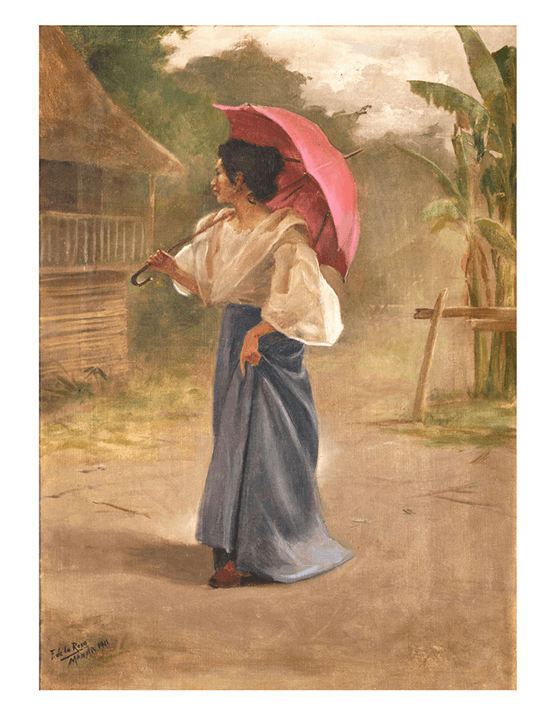

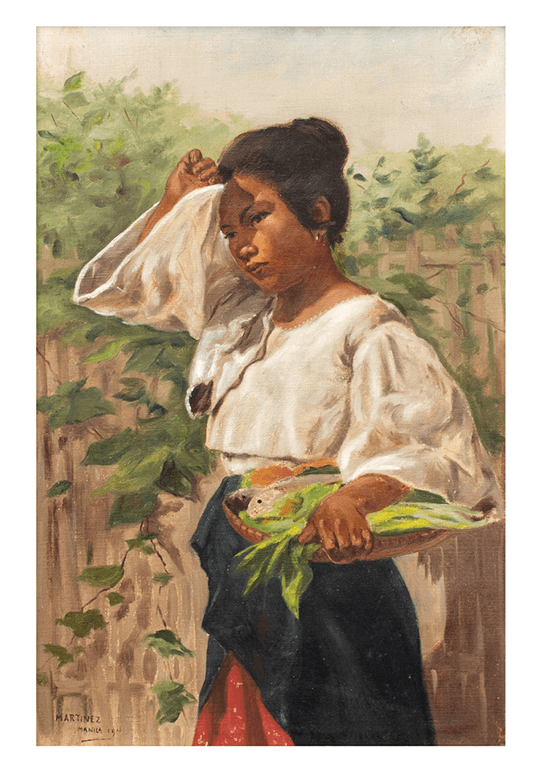

Bringing the auction full circle to the theme of muses and matrons, two wonderful artworks of busy women were met with enthusiastic acclaim: Fabian de la Rosa’s Filipina with a Red Parasol and Ramon Martinez’s Market Vendor. In combination with an azure and white baro and saya, the turn-of-the-century de la Rosa suggested the Filipino flag’s tri-color and brought in P4 million; a winsome woman, by Martinez, shading her face with a bell-shaped sleeve with one hand and holding a basket of produce with another took in P2.5 million handily.

Anita Magsaysay’s first-ever first-prize work, The Cooks, would set off a famous tug of war over its eventual ownership—with the influential columnist I.P. Soliongco on one side and an unnamed, honest-to-goodness market vendor from the Divisoria, who had, by dint of enterprise, made her own fortune and developed a taste for modern art. Guess who won that particular tussle?