Art for museum orphans and mall rats

These days, you get your art fix where you can find it.

In the good ol’ days, the guardians at the gate — the museums, the art fairs, the hoity-toity galleries — ran on the rarefied fumes of exclusivity. There were lines and waiting lists for everything; but there were also special passes and other antidotes given away, like slivers of bittersweet Royce chocolates, to the favored few. These let you jump the queues, cozy up to artists and, for those really in the winner’s circle, join the anointed to acquire rare works.

Like those mythical islands that appear only at low tide — and are swallowed up in the presence of a crowd — only the personages who could be certified to actually walk on water would be allowed to travel on these shifting sands of power and privilege.

Thus the time one could actually spend with the art was carefully calculated and, furthermore, limited according to this elitist arithmetic. You were in or out depending on how far ahead you were allowed in ahead of the general public. There were invitations to the “vernissage" (the prettified French term for a sneak-peek) and for their extra-strength version, even earlier “collectors’ previews.”

That, of course, all unraveled in the aftermath of the worst disaster on earth. Today, almost a year later, the art establishment is still left groping for the virus-proof art event that actually enlarges the experience rather than making it smaller.

Enter the art of the prequel. In Avengers and Star Wars parlance, that’s called the strategy of the story. For abstract art in particular, this can bring a transformative quality to the work, a backstory that can actually enhance it by drawing the viewer into its mystique. Annie Cabigting’s “100 Pieces” has one such origin story. And like every good superhero, a secret identity is involved. This one is steeped in the legend of a performance piece, the first of its name, the very first “Tearing into Pieces” by Robert Chabet, the ultimate “Joker” of conceptual art.

In late 1972, art writer Manuel Duldulao would produce his first art book ever, Contemporary Philippine Art. It was a two-kilo monster, with 300-plus pages and plenty of colored photographs, which was pretty much unheard of at the time because of prohibitive printing costs. It immediately raised the eyebrows of the art community and unconfirmed but deliciously ugly rumors swirled around it.

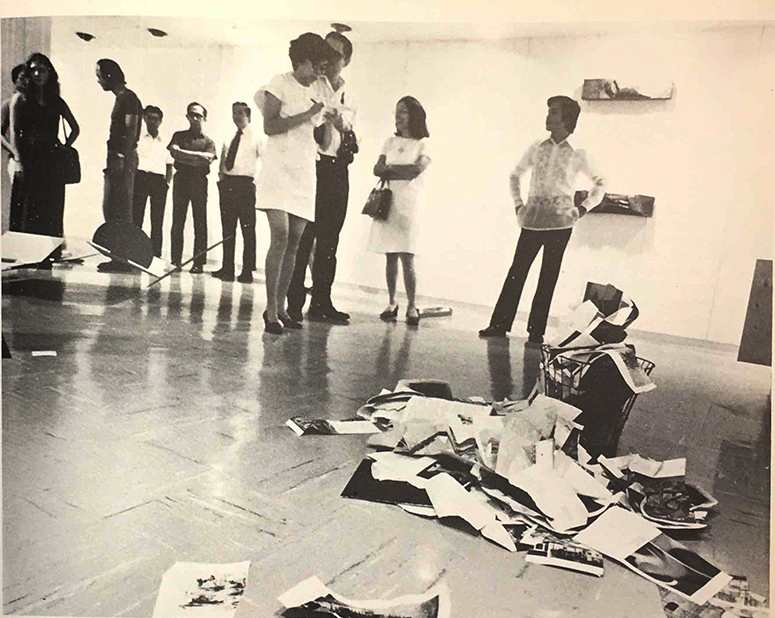

Enter Chabet, who decided to make his own statement on the book by making it the centerpiece of his newest work of art. That work had two parts: the first was a private performance piece during which he tore the book to shreds and then stood on his head in yoga poses on its crumpled pages. The second was a more public renunciation. He appeared at a prearranged time at the opening of a CCP exhibit, pulled the pages out of a paper bag, and stuffed them into a trashcan in the center of the Small Gallery. This would be Chabet’s indelible contribution to “An Exhibition of Objects” in January 1973, which is otherwise forgotten now. The spectacle caused a sensation.

Duldulao, a great promoter, had the presence of mind to find a photograph and publish it in his next coffee-table book. He gave what should have been proof of his shame a full page and credited the controversy for pushing the sales of his 1,000-book print run to sold-out status in just 10 days. (Don’t you dare ask me if I was there for any of this; all these details are from a wonderful account by Eva Bentchava which drew on the research of Ms. Ringo Bunoan and appeared in the Tate Museum’s digital archives.)

A little more than 30 years later, one of Chabet’s protégés, the then-unknown Annie Cabigting, would be working on her first-ever solo show, always a momentous occasion for any new artist. It presented the interesting opportunity to literally own one of Chabet’s defining moments and chart a new course for herself. Cabigting blew up the controversial photograph, cut it into 11” by 11” tiles, and then made dozens of different-sized icons of the woman captured taking notes of the whole “happening.” Each bit was painstakingly painted over so you’re not quite sure which is photograph and which is imagination. It was, of course, pure genius. This parable of spectatorship and what it means to art and the artists would go on to define Cabigting’s work for the rest of her career.

Looking to the international circuit, the annual Met exhibition has taken another approach. Attention has focused away from its high priestess Anna Wintour, who was also the inspiration for the swashbuckling editor in The Devil Wears Prada, and instead towards the more lovable movie stars, Nicole Kidman and Meryl Streep. The pair takes turns narrating passages from Virginia Woolf novels in the 2020 online edition of the Costume Institute’s show.

In terms of high-voltage Manila chic, nothing quite approaches Univers/Homme & Femme, purveyors of such lines as Rei Kawakubo’s Comme des Garcons and Virgil Abloh’s Off White. So perhaps it was not entirely unexpected that a foray into art would come to be. Chief collaborator is Migs Rosales who has a flame-proof reputation for intelligent high style. For its first exhibition, Univers founder Jappy Gonzalez decided to go in the direction of photography, primarily because it is an under-appreciated medium. A mix of photographers, in various stages of their careers, portrayed various stages of cool — or the Univers “point of view” — despite the pandemic. They are: Geric Cruz, Karen de La Fuente, Francisco Guerrero, Rachel Halili, Renzo Navarro, Carina Altomonte, Eric Bico, Everywhere We Shoot, Christian Halili and Veejay Villafranca. “Art Project/Series #1: Photographs” runs in the Univers retail flagship in One Rockwell till Dec. 24.

Finally, for all the museum orphans out there, there is the looking-glass experience. The young artist Norman Dreo specializes in the fetish-like adoration of these glorious institutions. His latest dazzling recreation centers on the Louvre and its major masterpieces, including its hoard of Leonardo da Vincis. Recreating it is just the thing to tide you over while the biggest museum in the world has been laid low. Pre-pandemic, the French national museum was a magnet for over 10 million visitors a year — 70 percent coming from outside France, in particular a swarm of tourists from America, China, and the rest of Asia. Whip out those calculators, now: a ticket to the Leonardo da Vinci show, the last of the Louvre’s blockbusters before the quarantine, would have rung in hundreds of millions of euros at the till, with tickets priced at 17 euros (or P1,000) each.

All that income is gone now and, replacing it, a necessary rethinking of the future of such great palaces of art. Sure, the Louvre is also the most beloved museum in the world on social media with 2.5 million fans on Facebook and 4.3 million followers on Instagram. But as any of this clamoring horde can tell you, nothing compares to an up-close-and-personal, face-to-face audience with the “Mona Lisa,” to be clucked over and regrammed into meme eternity.

In Dreo’s world, all these experiences can now be brought alive. He’s hit upon his own concept of continuity which was the end goal of traveling thousands of miles to make a pilgrimage to these altars of high art sans the long lines and VIP cards. It also taps into the same community of artists and gallery-goers to which Cabigting has tethered her own art. However, while Dreo travels a democratic path, and Cabigting a route intended for the cultural cognoscenti, they both wind up in the same place: an appreciation of art no matter the consequences.

* * *

Both Annie Cabigting’s “100 Pieces” and Norman Dreo’s “Journey to the Louvre I and II” are highlights of the León Gallery Kingly Treasures Auction on Nov. 28. The Univers Art Project is at Rockwell Power Plant Mall until Dec. 24, open Sunday to Thursday, 11 a.m. to 7 p.m., and Friday to Saturday 11 a.m. to 8 p.m.

Banner caption: Norman Dreo, “Journey to the Louvre I and II”