Galleons and talismans

It’s a pity that the Asian Civilizations Museum chose to close their “Manila Galleon” exhibition just before Holy Week and the second most important Catholic holiday, Easter Sunday. It would have attracted scads of pious Manilans who would have preferred to worship at that shrine if they had stayed open. (Certainly, they would have been a little more scholarly than the Taylor-Swift-singing hordes that flocked to its shores.)

Singapore was purportedly on the route of the great galleon trade although it had still to be invented by the British as a colony. The nearby outposts were in the nefarious business of lighting fires to lead astray unsuspecting Spanish ships—already famous for bearing silver, silk mantons, chests encrusted with ivory and pearls, and the assorted riches of the east. Think of it as a case of spoofing, like today’s deep fakes created by AI, intended to lure ship captains into mistaking the fires for lighthouses and safe havens.

Enter one of the Philippines’ most beloved icons, Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage, which is now berthed in the Antipolo cathedral. Recounts cultural historian Augusto “Toto” M. R. Gonzalez III: “It was brought from Mexico in 1626 and was loaded on six different galleons to ensure their safe—and most importantly, profitable—Manila-Acapulco crossings from 1648-1748. Our Lady was first enshrined in a church in the area of the current town of Antipolo.” But the image, he said, “would keep on disappearing from the altar, eager to keep traveling and reappear on top of a “tipulo” tree (Artocarpus incisa, or breadfruit tree). The Jesuits finally relented and simply built a church on the site. Gonzalez maintains that “Many scientifically inexplicable favors and healings were granted to devotees through her intercession. From its arrival in the 1600s, through the 1700s to the 1800s, to the present day, the image has had a strong cult following.”

The Virgin Mary as an endorser of cigars, cigarettes, and smoking? Only in the Philippines.

Historian Ambeth Ocampo has reported that he routinely “packs in his hand-carried luggage with his medicines... the small bronze image of the Virgin of Antipolo, circa 1900s, presented by La Germinal tobacco company to loyal customers.” He asks further: “The Virgin Mary as an endorser of cigars, cigarettes, and smoking? Only in the Philippines.” The image traveled with him serendipitously on his own journey to lecture at the Galleon show. I’ve been meaning to tell him that La Germinal was the cornerstone of the fortune of Ariston Bautista Lin, the third man in Luna’s magnificent painting “Parisian Life” (alongside Jose Rizal and Luna). He built the house that is now known as Bahay Nakpil where the painting once hung—and yes, he was the country’s first pulmonologist, of course, at a time, when tobacco was actually considered medicinal. Dr. Bautista was also one of the original ilustrados and would have himself brought the miraculous Virgin’s images with him on his travels to Madrid and Paris.

Indeed, Gonzalez notes, “Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage made six immensely successful, profitable Pacific crossings over a hundred years, the better to venture to Singapore with! She was certainly a good luck charm to the Spanish.”

Perhaps the other most popular Blessed Virgin image is Our Lady of the Rosary in Manaoag: It was also supposed to have come aboard a galleon from Mexico in the early 1600s, says Gonzalez, who emphasized that this, however, “is debatable because it is a local image of hardwood and ivory and has several analogs in Northern churches.” In 1610—as legend would have it—he relates, “A farmer was walking (again, in the area of current Manaoag) and saw a vision of Mary and the Child Jesus on top of a tree calling him out to have a church built on the site.”“Manaoag” is derived from “mantaoag” in the local dialect, this chronicler says, which means “to call.” “Many scientifically mysterious favors and healings continue to be granted to devotees who visit it to seek guidance and succor,” he writes. “From its first appearance in the early 1600s, it has always had a strong cult following within Pangasinan. But since the 1980s, the cult has expanded nationwide.”

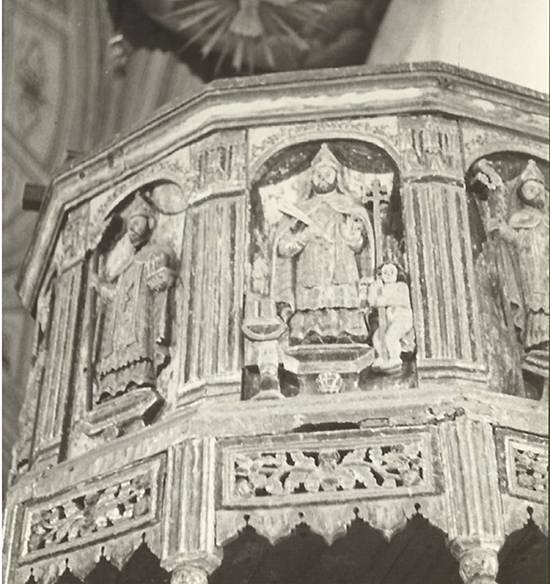

The Philippines, of course, has an insanely rich cultural history, of which the Manila Galleons are just a very small fraction. One object of public fascination happens to be the Buljoon panels of the Patrocinio de Maria Santissima Church in Cebu. It depicts vignettes from the life of St. Augustine of Hippo. A philosopher of Berber origin, he had the kind of mind in which the concepts of “the City of God” and “a just war” could co-exist very neatly. Five of the original carved relleves went missing sometime in the 1980s. (One was left behind and is now under lock and key in the parish museum.) There is a tug of war over these spectacular objects between the Province of Cebu and the National Museum but what matters is, either way, they are now in safe custody.

May all the saints and martyrs, totems and talismans protect us on all life’s journeys as assiduously as the assembled Virgins have done through centuries of our history.