Culture

YES to a more livable life

The leader we need isn’t someone who is necessarily in the service of culture and the arts in the rudimentary sense. Not someone who can manufacture sparkly new buildings and award-giving bodies that valorize the work of a few. The leader we need is someone who can genuinely improve the material conditions of the masses from which many artists emerge.

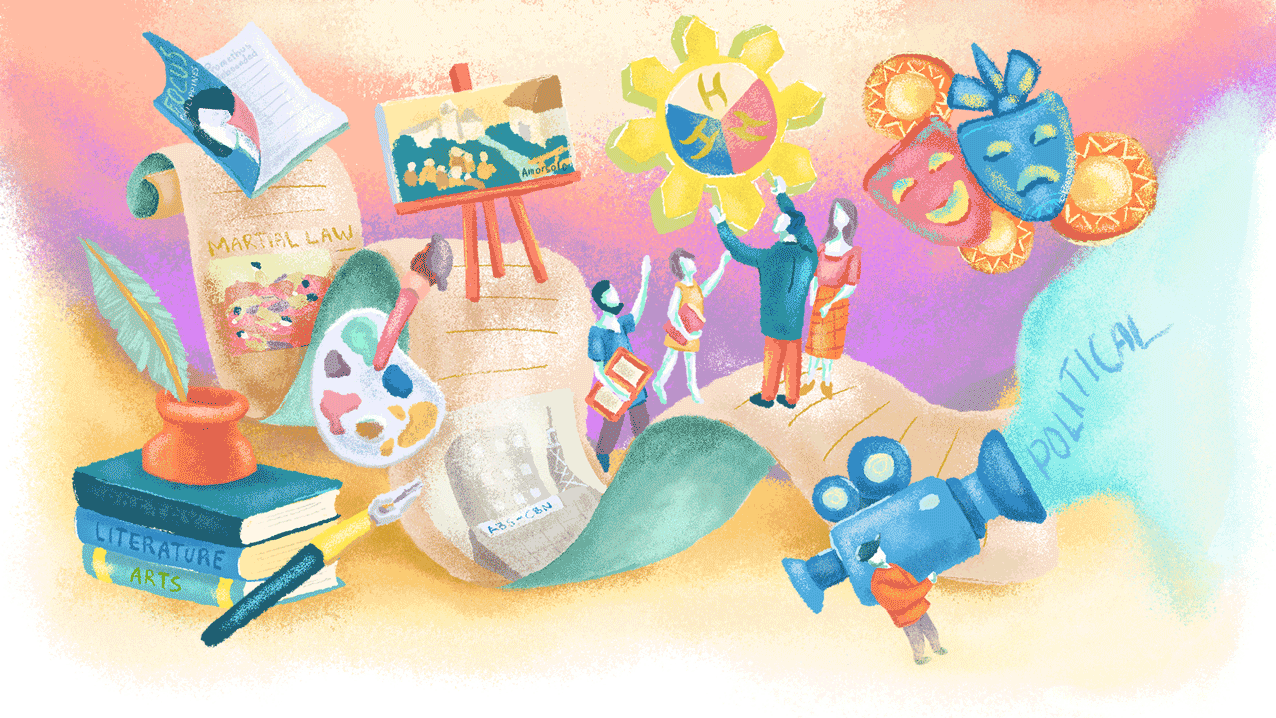

In 1972, the National Artist Award was first conferred, posthumously, to Fernando Amorsolo, known for his social realist depictions of rural Philippines. This happened at the onset of the martial law, six years into what would become a 21-year dictatorship.

By 1973, writing under the pseudonym Ruben Cuevas, Pete Lacaba’s Prometheus Unbound was published in Focus Philippines. Initially interpreted as a simple ode to Percy Bysshe Shelley’s four-act lyrical drama of the same title, the poem turned out to be an acrostic in which the first letter of each line spelled out “Marcos Hitler Diktador Tuta.”

There it was: a well-known protest slogan smuggled right into state-sanctioned literary pages.

For most parts, the martial law is remembered for the Marcoses’ blatant human rights abuses—tortures, killings, desaparecidos and whatnot. Amidst all this, however, there are still some who insist on glorifying the period for its supposed cultural and artistic prosperity.

By 1976, the same National Artist award was conferred to writer Nick Joaquin who famously used it as bargaining chip against the Marcoses. In exchange for his acceptance, Joaquin lobbied for the release of Lacaba who was illegally detained in 1974 for his role in the resistance movement. Lacaba was freed shortly thereafter.

I write this now while sitting placidly in my one-bedroom apartment, my unpublished poetry manuscript collecting dust somewhere in my computer. Over three decades since the Marcoses were removed from power and with a global health crisis upon us that has conveniently served as smokescreen for increased militarization, I wonder what role art and culture, and by extension, artists and cultural workers play in our time of heightened precarity.

I think about my own silly little poems and wonder what impact they make to actual, material struggles felt squarely by those on the fringes. I think about abject poverty and hunger, which cannot be remedied by the beauty and brilliance of craft. I think about the killings, the tortures, the disappearances happening amidst so-called artistic wealth. So why then must presidents care so much about art and culture? It seems the late dictator had an answer.

Co-opting the artist’s imagination

We have seen how partisanship has played in the award-giving process across many administrations, which means artists vying for the award are inclined to stay within the good graces of the sitting president. Being conferred into this order, after all, entitles one to a slew of life-long benefits akin to those received by the highest officers: economic security usually absent in an artist’s career.

To confer artists into this order is to keep our generation’s storytellers beholden to the benevolence of the state. It is to co-opt not only the imagination and authority of the artist, but also their ideological representations (such as the case for Amorsolo and whatever proletarian notions, if any, are espoused in his work).

The National Artist award, more than anything, is a Marcos invention used to subjugate the cultural and intellectual capital of artists. If art truly has the power to shape the Filipino consciousness, it is therefore in the interest of governments to maintain friendships with those who they deem and insist are most artistically gifted.

As the presidential election draws closer, we are forced to interrogate our role not only as producers of art but as people who negotiate using the cultural currency bestowed uniquely upon 'artists.' More importantly, we need to blur the distinctions between who we are as artists and who we are as wage workers, laborers, etc., lines that make us think we are immune to our country’s shared oppression.

And the title has certainly served this purpose. In 2020, F. Sionil Jose who was conferred in 2001, publicly expressed support for some of the state’s most insidious rulings, including the shutdown of the country’s largest media outfit. In his write up, he argues that “the Filipinos do not really need ABS-CBN. It does not produce goods or food. It has certainly entertained millions but it did not diminish poverty. Again, freedom worked for the rich—but not for the Filipinos.”

While he must have spoken from the position of an ordinary citizen, there stood his title in bold font across many headlines, effectively legitimizing his dangerous ideas: National Artist F. Sionil Jose in favor of ABS-CBN shutdown.

He isn’t incorrect in his assertions against the elite, but the same case can certainly be made against the National Artist title itself. In fact, for all its scholarly value, the works of National Artists have largely remained inaccessible to the masses, serving only the interest of middle and upper-class Filipinos.

This isn’t to say all National Artists are complicit. It is far from that. Filmmakers Lino Brocka and Ishmael Bernal were known for smuggling political messages in their films. Bienvenido Lumbera has written extensively against the Marcos dictatorship. The list goes on. This is simply to say that we have to remain critical in examining the title’s assumed intellectual infallibility.

The leader we need

As the presidential election draws closer, one can’t help but question one’s complicity in the prestige-sharing practice between public official and artist. We are forced to interrogate our role not only as producers of art but as people who negotiate using the cultural currency bestowed uniquely upon “artists.” More importantly, we need to blur the distinctions between who we are as artists and who we are as wage workers, laborers, etc., lines that make us think we are immune to our country’s shared oppression.

In the words of poet Conchitina Cruz, “There is something amiss in collective action when all that comes out of it is more poetry.” This means we must take part in the larger political life that exists outside of craft. Through this, we gain a better sense of historical consciousness that informs our work and in participating in collective struggle, we are emboldened to create work that is meaningful, liberating, and emancipatory for others.

The leader we need, thus, isn’t someone who is necessarily in the service of culture and the arts in the rudimentary sense. Not someone who can manufacture sparkly new buildings and award-giving bodies that valorize the work of a few. The leader we need is someone who can genuinely improve the material conditions of the masses from which many artists emerge. The only way anyone can tangibly support the arts, especially when it comes to alternative voices reared from the country’s working class—not only from the sheltered clusters of the educated elite—is in rendering a more livable life.

There is no doubt that the country is going through a historical period, one whose political context can be likened to the Marcos era. In deciding who gets to lead our country in 2022, we need to imagine better alternatives to the cards we are periodically dealt with. And in the grand tradition of imagining worlds beyond our own, may the artist espouse and inspire a freer Filipino consciousness.

Every voice matters. Register now! Go to irehistro.comelec.gov.ph.