Urbanism

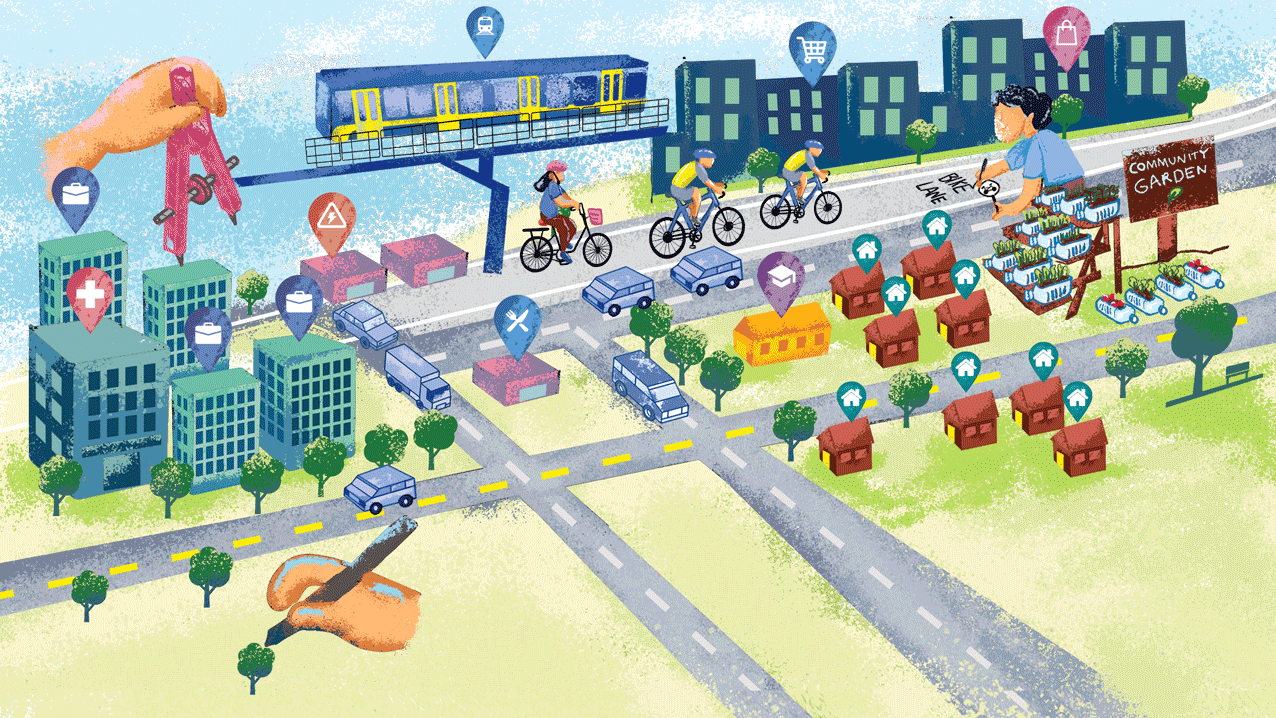

YES to leaders who share the MRT or bike lanes with the Filipino people

We hope for leaders who tread on the same hard concrete, who share the scents and sweat of walking the city, who eat goto and turo-turo food who spend time with and listen to the less visible and more vulnerable communities. We need leaders who live like the rest of us, so they know how much we desperately need greens in the metro, how so many still need basic necessities, and how much all of urban life feels every day.

2022 is drawing near, and many horrors continue to cast shadows on Philippine urban spaces and communities.

Urbanists could promptly recite a litany of concerns: incredibly long queues of pedestrians waiting for public transport; the backward new expressways and other "utak-semento" projects and policies; rigid, fragmented zoning practices; "developments" causing dispossession in our fringes; the perpetual “need for resilience and sustainability” in projects laced with development lingo; urban activists who find their place in a constant struggle; the lack of urban imagination and information in bureaucratic “planning;” starchitects flaunting greenwashed visuals and writing truisms; professional turfing—the list goes on.

Recent responses to pressing issues, especially those borne by the drug war and the pandemic, have shown how regressively we tackle the urban: slums are the drug war scenery, blanket lockdowns are imposed, walls are in the middle of roads, and mega-vaccination sites are preferred over potential urban forest parks.

Scholars would point out how our urban concerns today are colonial vestiges; practitioners or business people would be more concerned about moving forward and finding opportunities in real estate, transport, design, and development; and urban dwellers would simply want to have livable places, where it’s easy to move between home and the workplace, or where they won’t be branded pasaway for activities they need to do to survive.

Understanding the complexity and nuances, and addressing them, are part of good urban leadership.

Value in multiplicity

Urban leaders are not limited to local executives, or planners inside the city hall, or licensed professionals. Leaders can be found in the young lady who can spark a nationwide community pantry movement overnight, or in any urban dweller who organizes, or is active in debates, or plants a shared garden, or takes to social entrepreneurship, or who takes time to listen to the people they meet every day.

But to those we hold accountable to their office, we expect so much more. Leaders need to be more intelligent and progressive, and unafraid to talk about issues that are difficult, such as addressing informality beyond the “street clearing” or resettlement that goes with the rebranding and cleanliness. Or combatting patriarchy, which manifests in presidential speeches all the way to the hard infrastructure of our environment.

There is a quiet strength in how leaders admit their own weaknesses and seek to improve, in placing value in the capacities and intelligence of others, and in seeking the relationships and smaller networks of solidarity that are otherwise omitted in traditional politics, the grandiose building programs, and in planning and policy-making.

Leaders have to have the drive to work on systemic changes, and have to be critical about our planning systems and the laws that create them. I imagine future leaders who will invest in urban research and creative opportunities, who will undertake urban transformations (sans the highways), especially in the public realm.

More importantly, I hope for leaders who frequently share the MRT or the bike lanes with the Filipino people. Leaders who tread on the same hard concrete, who share the scents and sweat of walking the city, who eat goto and turo-turo food who spend time with and listen to the less visible and more vulnerable communities. We need leaders who live like the rest of us, so they know how much we desperately need greens in the metro, how so many still need basic necessities, and how much all of urban life feels every day.

This change comes with empathy, respect, care, and a keen sense for listening and collaboration. Some equate or degrade this leadership to be soft, or “not enough,” and prefer to rely on “toughness” and control, yet there is so much more beyond the parade of generals and hostile “gunpowder thinking.”

There is a quiet strength in how leaders admit their own weaknesses and seeks to improve, in placing value in the capacities and intelligence of others, and in seeking the relationships and smaller networks of solidarity that are otherwise omitted in traditional politics, the grandiose building programs, and in planning and policy-making.

We approach another point in history where we can provide the platform for others to create change; hopefully, this time, we see more leaders who are feminist, and knowledgeable about the urban.

Every vote counts. Register now! Go to irehistro.comelec.gov.ph.